Evaluation of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative

Publication information

Ce document est disponible en français.

Office of Internal Audit and Evaluation

Parks Canada

30 Victoria Street

Gatineau, QC J8X 0B3

©His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, represented by the Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada Agency, 2025

CAT. NO TBA

ISBN TBA

Table of contents

- List of tables

- List of figures

- List of acronyms and abbreviations

- Introduction

- Acknowledgment and context

- Program profile

- Key findings: Relevance

- Key findings: Relationships

- Key findings: Effectiveness

- Key findings: Sustainability

- Key observations

- Annex A: Crosswalk of UNDA and the Indigenous Stewardship Framework

- Annex B: Transfer payments to Indigenous recipients

- Annex C: Bibliography

Title: Evaluation of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative

Organization: Parks Canada Agency

Date: April, 2025

List of tables

| Number | Titles |

|---|---|

| Table 1 | Acronyms and Abbreviations |

| Table 2 | Harvesting |

| Table 3 | Governance |

| Table 4 | Cultural Continuity |

| Table 5 | Indigenous Knowledge |

| Table 6 | Apologies and Acknowledgments |

List of figures

| Number | Titles |

|---|---|

| Figure 1 | Timeline of Key Phases in Indigenous Relationships with Parks Canada |

| Figure 2 | Parks Canada Indigenous Stewardship Framework |

| Figure 3 | Organizational Structure of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative |

| Figure 4 | IGI Projects by Region 2021-22 to 2025-26 |

| Figure 5 | IGI External Approved Projects, Actual and Planned Expenditures, 2021-22 to 2025-26 |

| Figure 6 | IGI External Approved Projects by Region, Actual and Planned Expenditures, 2021-22 to 2025-26 |

| Figure 7 | Indigenous Stewardship Framework and Parks Canada’s UNDA Measures |

| Figure 8 | Sample of Indigenous Guardians Initiative Funding Agreements by Type (2022 – 2024) |

| Figure 9 | Rating of the Likelihood of Impacts Related to the Sunsetting of the IGI |

List of acronyms and abbreviations

| Acronyms | Names in Full |

|---|---|

| IGI | Indigenous Guardians Initiative |

| ISF | Indigenous Stewardship Framework |

| IGP | Indigenous Guardians programs |

| UNDA | United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act |

| GCGCP | General Class Grants and Contributions Program |

| WCT | West Coast Trail |

Introduction

Consistent with the requirements of the Treasury Board Policy on Results (2016) and associated Directive on Results and Standard on Evaluation, the evaluation of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative examines the impacts of Indigenous Guardians programs at Parks Canada-administered places as well as the relevance, effectiveness, relationship-building, and sustainability of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative (IGI).

Evaluation scope

Reflecting the diversity of Indigenous Guardians programs (IGPs) currently operating and in development, the scope of the evaluation includes both long-standing Indigenous Guardians programs and those recently created with the support of the IGI, a five-year initiative aimed at enhancing existing IGPs and fostering the development of new partner-led programs. As such, while the evaluation is primarily focused on activities and results between 2021-22 and 2024-25, longer-term impacts will also be considered.

To reflect these distinct scoping elements, the evaluation was divided into two components:

- An internally-focused evaluation, led by Parks Canada, assessing the implementation of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative to date; and,

- A study of the impacts of Indigenous Guardians programs led externally by consultants specializing in Indigenous evaluation.

Report overview

This report presents the key findings of the internally-focused evaluation of the IGI, addressing its relevance, sustainability, effectiveness, and relationship-building dimensions. Field work supporting the evaluation’s lines of evidence was conducted between August 2023 and July 2024.

Acknowledging the partner-led nature of IGPs, this evaluation did not examine the performance of individual programs, the aims of which are determined by the values and priorities of Indigenous communities and their governments.

Evaluation Questions

- Does Parks Canada’s approach to IGPs contribute to positive relationships with Indigenous governments and organizations?

- To what degree have internal structures and processes effectively supported the implementation of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative? What challenges have been identified?

- To what extent are the IGPs aligned with UNDA and Parks Canada's priorities regarding Indigenous Stewardship?

- To what degree are strategies in place to address programs' sustainability over the medium and long-term?

Data collection

Data from multiple lines of evidence were collected and analysed. These included:

- A review of academic literature on Indigenous Guardians programs in Canada and internationally;

- A file review of contribution agreements related to the Indigenous Guardians Initiative (Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreements were not included in the sample);

- Key informant interviews with Parks Canada staff;

- A review of financial data related to the Indigenous Guardians Initiative; and,

- A survey of field unit staff supporting Indigenous Guardians programs at Parks Canada-administered places.

Note on the Indigenous Stewardship Policy

Parks Canada enacted a new Indigenous Stewardship Policy in the fall of 2024, guiding the implementation of both Parks Canada’ Indigenous Stewardship Framework and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (2021).

While relevant to the work of Indigenous Guardians, this policy came into force in the final reporting phase of the internal evaluation. Policy elements were incorporated into findings and observations as appropriate.

Acknowledgment and context

Indigenous Peoples and national parks

For millennia, Indigenous Peoples have cultivated reciprocal relationships with lands, waters, and ice guided by cultural practices, values, and knowledge systems.

Beginning in the 19th century, the development of national parks and protected areas in Canada disrupted these relationships through exclusion and colonial injustices. In establishing national parks (see Figure 1 below), Indigenous Peoples were forcibly removed from their homes, denied access to traditional territories, and prohibited from hunting and harvesting on park lands. With parks created without the involvement of Indigenous Peoples, communities were denied the opportunity to make decisions about land management and resource use.

These laws, practices, and policies caused historic and ongoing harm for Indigenous communities. They eroded Indigenous systems and protocols for engaging with each other and contributed to the complexity of historic and ongoing relationships between Indigenous governments.

Parks Canada now acknowledges this harmful historical legacy and its impact on Indigenous language, culture, laws, and governance systems and has committed to developing healthy relationships with First Nations, Métis, and Inuit partners to support Indigenous stewardship and self-determination.

Indigenous Guardians programs, alongside other inclusionary practices such as co-management and Indigenous protected and conserved areas, have emerged internationally as one means for Indigenous Peoples to reassert jurisdiction over their ancestral territories and seek to fulfill their responsibilities as stewards. These programs are known by several names including Guardians, Rangers, Watchmen, Earth Keepers, and Beach Keepers.

Text description

Figure 1: Timeline of Key Phases in Indigenous Relationships with Parks Canada

Timeline of Key Phases in Indigenous Relationships with Parks Canada.

The timeline begins in 1887 and ends in 2024.

Heading: Protected Areas, Displaced People.

1897: Stoney Nakoda prevented from using land as in past ways.

1897: Banff National Park established as first national park.

1911: Parks Canada Agency founded as the Dominion Parks Branch.

1930: Keeseekoowenin First Nation removed from their lands.

1930: Riding Mountain National Park established.

1943: South Tutchone denied access to harvesting.

1943: Kluane Game Sanctuary created.

Heading: Policy and Practice in Transition.

1974: National Parks Act amended; parks can be established as "reserves" until land claims resolved.

1981: Haida Gwaii Watchmen Program founded by the Skidegate Band Council.

1982: Constitution Act recognizes and reaffirms aboriginal and treaty rights.

1995: Pacheedaht, Ditidaht, and Huu-ay-aht First Nations co-found the West Coast Trail Guardians.

2000: Canada National Parks Act prioritizes relationships with Indigenous partners.

Heading: UNDRIP and Rights Recognition.

2007: United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

2015: Adoption of "PARKS" Principles for work with Indigenous partners.

2021: Indigenous Guardians Initiative to support the development of 30+ Guardian programs.

2021: United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.

2023: UNDA Action Plan.

2024: Parks Canada Indigenous Stewardship Policy.

Legal and policy frameworks

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) is a comprehensive international instrument enshrining the rights of Indigenous Peoples. A product of almost 25 years of advocacy from Indigenous leaders in Canada and across the world, UNDRIP details both individual and collective rights for the survival, dignity, and well-being of Indigenous Peoples.

The declaration includes protections for environmental, cultural, and economic freedoms. Key themes include self-determination and freedom from discrimination; free, prior, and informed consent; and the right to practice and revitalize cultural traditions and customs.

UNDRIP was formally adopted by the Government of Canada in 2016.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act

Coming into force in June 2021, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (UNDA) advances the implementation of UNDRIP in Canada at the federal level.

The Act requires the Government of Canada to take all measures necessary to ensure Canadian law is consistent with UNDRIP. It mandates the creation of an action plan for the Government of Canada to work with Indigenous partners to implement the principles of the UNDRIP.

After two years of consultation with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis partners, the UNDA Action Plan was released in 2023, as a whole-of-government, five-year plan for the Government to align with its UNDRIP commitments and meet the legislative requirements of UNDA.

Of the 181 Action Plan items, Parks Canada is responsible for five measures which aim to recognize and enable Indigenous Peoples’ rights and responsibilities in stewarding lands, water and ice within their traditional territories, treaty lands, and ancestral homelands. These measures are:

- 35. Harvesting by Indigenous Peoples

- Governance

- Cultural continuity

- Indigenous knowledge

- 110. Apologies and acknowledgements.

Commitments to Indigenous Guardians programs feature in UNDA action plan measures 35 and 96. Under the Harvesting measure, IGPs are proposed as a mechanism for supporting and enforcing the exercise of Indigenous harvesting rights. Under Cultural Continuity, “enhanced and sustainable” IGPs feature in commitments to on-the- land cultural and language learning, economic revitalization, and the promotion of public education to build understanding of Indigenous stewardship (See Annex A, Crosswalk of UNDA and the Indigenous Stewardship Framework).

Parks Canada Indigenous Stewardship Policy

The Indigenous Stewardship Policy was enacted in ceremony on October 15, 2024. The policy guides the implementation of Parks Canada’ Indigenous Stewardship Framework (see next page) as well as UNDRIP and directs responsible Parks Canada executives to co-develop site- specific stewardship plans as well as stewardship strategies for each of Parks Canada’s directorates.

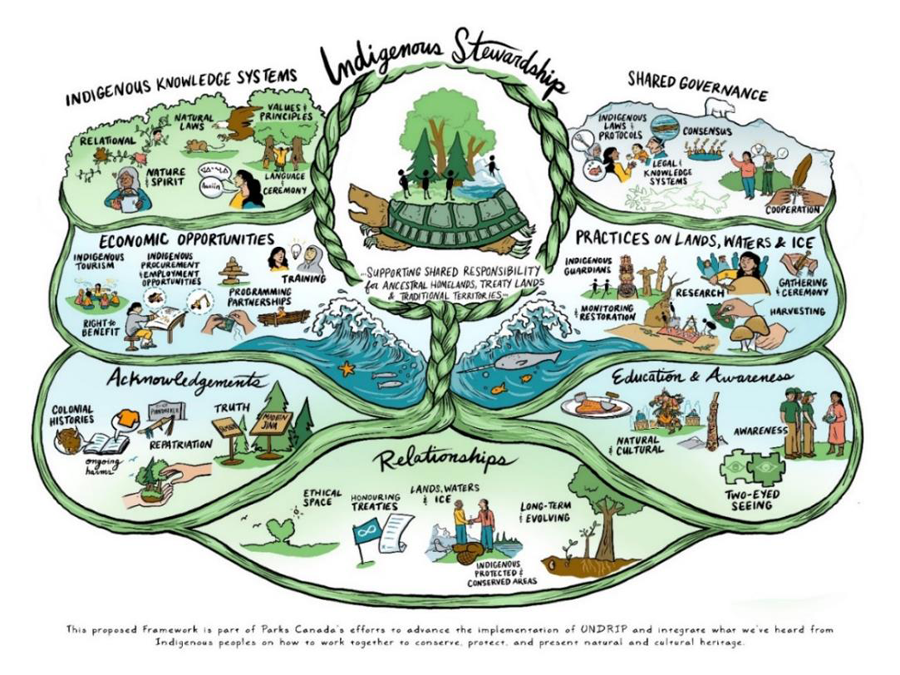

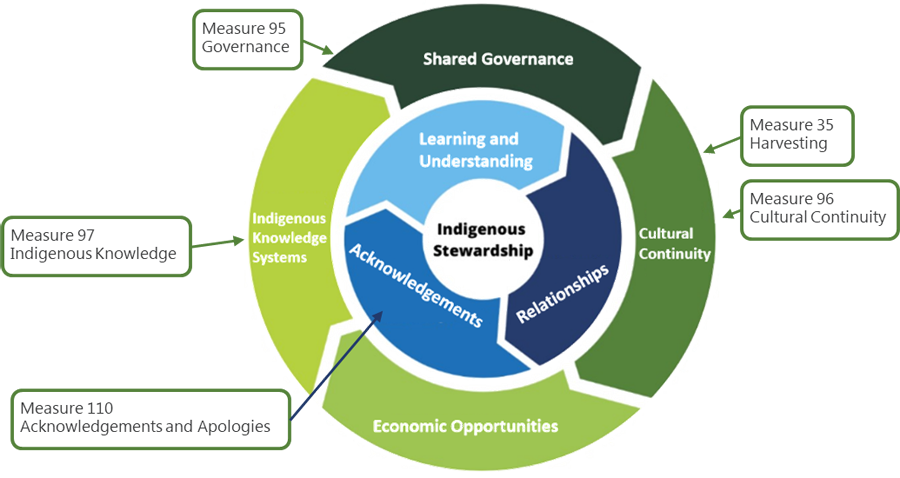

Indigenous Stewardship Framework

The Indigenous Stewardship Framework (ISF) reflects what Parks Canada has heard from Indigenous Peoples over many years on what is needed to support Indigenous (re)connections with lands, waters, and ice within traditional territories, treaty lands, and ancestral homelands.

The ISF consists of seven interrelated elements. Four of these, Shared Governance, Cultural Continuity (also called Practices on Lands, Waters, and Ice), Economic Opportunities, and Indigenous Knowledge Systems are considered central components of Indigenous stewardship. Three more elements, Acknowledgment, Apologies, and Redress; Relationships; and Learning and Understanding are considered necessary foundations for supporting Indigenous Peoples in exercising their stewardship responsibilities.

Together, these seven elements are intended to provide a path forward in aligning Parks Canada legislation, policy, and operational practices with UNDRIP.

The ISF is supported by the Indigenous Stewardship Circle, a diverse group of Indigenous leaders external to Parks Canada who provide ongoing guidance and direction. The work of the Circle is grounded in Ethical Space, where all knowledge systems are equal and interact with mutual respect, kindness, and generosity.

Text description

Figure 2: Parks Canada Indigenous Stewardship Framework

Illustration of the Indigenous Stewardship Framework.

The Indigenous Stewardship Framework consists of seven interrelated elements.

Four of these, Shared Governance, Cultural Continuity (also called Practices on Lands, Waters, and Ice), Economic Opportunities, and Indigenous Knowledge Systems are considered central components of Indigenous stewardship.

Three more elements, Acknowledgment, Apologies, and Redress; Relationships; and Learning and Understanding are considered necessary foundations for supporting Indigenous Peoples in exercising their stewardship responsibilities.

Program profile

Indigenous Guardians Initiative

Funding for the Parks Canada Indigenous Guardians Initiative (IGI) was allocated under Budget 2021 as part of a wider $173 million plan to support Indigenous Guardians programs in partnership with multiple federal entities. Within that, Parks Canada received $61.7 million to be invested between 2021-22 and 2025-26.

The main objective of the IGI is to support the development of between 30 and 35 new or enhanced partner-led programs linked to Parks Canada-administered places, i.e., national parks, national park reserves, the national urban park, national marine conservation areas, and/or national historic sites.

Program design

Goals and outcomes of each individual program are determined by Indigenous partner organizations according to their interests and priorities. Co-development of new programs typically follows a four-part phased approach, with each phase building a foundation for the next.

Explore: This involves scoping and planning activities to identify the potential for a Guardians program. Projects in this phase can include community engagement sessions, needs assessments, and preliminary discussions to determine scope and objectives.

Capacity building: This focuses on communities growing capacity in identified areas. Projects in this phase may include specific training, experiences on the land, traditional and cultural knowledge sharing, and hiring of a program coordinator to outline next stages.

Implementation: The actual launch of the program, this phase sees the hiring and training of staff, the creation of operational procedures, and the start of stewardship activities. These often include ecological monitoring, cultural site protection, community outreach, and/or the implementation of Indigenous knowledge and conservation practices.

Sustain: This involves supporting an ongoing program beyond its initial implementation. Projects during this phase may include implementing best practices and lessons learned, enhancing the scope and capacity of the program, and engaging in future planning.

While these phases are used to track the development of Guardians programs, funding agreements may reflect one or multiple phases. Projects and their related expenditures in each phase are not mutually exclusive.

Funding agreements

A variety of funding mechanisms have been used over time to distribute funds to Guardians programs at Parks Canada-administered places, such as contracts, contribution agreements, grants, and micro-grants. At present, IGI funds for program development, implementation, and operation are transferred to field units and then to Indigenous partners using the authorities of Parks Canada’s General Class Grants and Contribution Program (GCGCP).

Governance and management

Indigenous Guardians programs linked to Parks Canada-administered places, while typically developed in collaboration, are implemented and managed by Indigenous governments or organizations.

Prior to the start of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative, existing Guardians programs relied on funding allocated from within field units’ baseline budgets. Long-standing programs had, until recently, mostly used contracts to distribute funds, alongside in-kind supports such as joint training activities. Then, as now, relationships with Indigenous governments were held by local field unit staff.

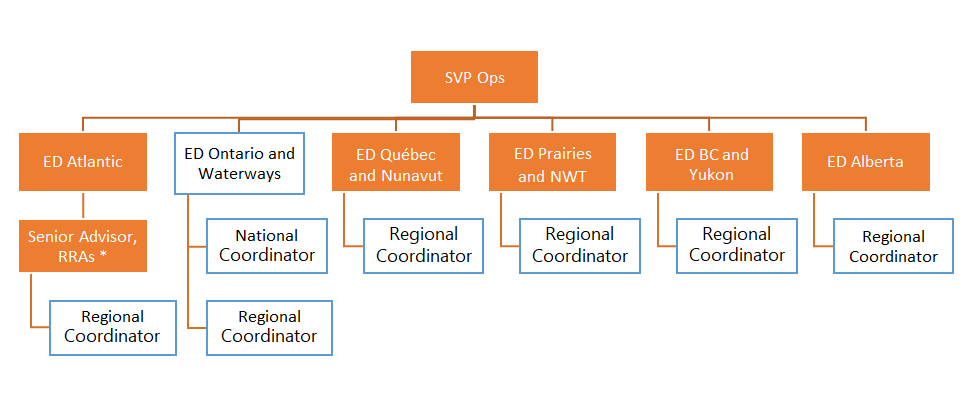

Since 2021, the IGI has been administratively located within Parks Canada’s Operations Directorate. Led by the Senior Vice-President, Operations (SVP Ops) the Directorate plans and implements the activities needed for the daily functioning of Parks Canada-administered places.

Six Executive Directors (EDs) report to the SVP Ops and are responsible for the alignment of regional operations (i.e., field unit activities) with Parks Canada strategies and priorities. The IGI essentially mirrors this model with its organizational structure (see Figure 3 below), which includes one National Coordinator, reporting to the ED Ontario and Waterways, and six Regional Coordinators who report to their corresponding Executive Directors, or to staff within the Executive Director Offices.

Regional Indigenous Guardians Coordinators support field units in working with partners to develop new programs, or enhance existing ones, by clarifying IGI goals, sharing information and tools, and helping to prepare funding applications for approval. The National Coordinator oversees the IGI funding, reviews and recommends funding proposals and contribution agreements and disseminates information to the regional coordinators through regular meetings.

Funding approvals

Once Indigenous organizations have explored the possibilities of a new or enhanced program, a proposal is developed by the Indigenous partner with support from field unit staff and/or the Regional Guardians Coordinator. This includes descriptions of project goals, budgets and plans, as well as a risk analysis based on the project and the partner organization’s capacity levels. The Operations Directorate Management Committee is the approval body for funding proposals.

Text description

Figure 3: Organizational Structure of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative

Image of organizational chart for the Indigenous Guardians Initiative.

SVP Ops manages the IGI.

Six Executive Directors (EDs) report to the SVP Ops and are responsible for the alignment of regional operations (i.e., field unit activities) with Parks Canada strategies and priorities.

One Regional Coordinator reports to each of the six Executive Directors (EDs).

One National Coordinator reports to the ED Ontario and Waterways.

One Senior Advisor, Reconciliation and Rights Agreements reports to the ED Atlantic.

*Rights and Reconciliation Agreements

New and enhanced IGPs to date

As of November 2024, the Indigenous Guardians Initiative reported a total of 37 new or enhanced IGPs in the Implementation or Sustain phases of development, as well as an additional five programs in the Capacity Building phase. Seven active projects were also reported in the Explore phase, each of which may or may not evolve into new IGPs (see Program profile for descriptions of the IGI phases).

Tracking the development of new IGPs through the Indigenous Guardians Initiative’s four phases is largely based on a review of approved projects with Indigenous partners. These fund activities ranging from initial community engagements to fully operational programs. However, as noted above, funded IGI projects are not exclusive to these development phases, as the path followed by each Indigenous partner is unique to their needs and interests. Multiple projects may be needed to move one partner from Explore to Capacity Building, while a single project funded through a multi-year contribution agreement may cover an IGPs’ Implementation and Sustain phases.

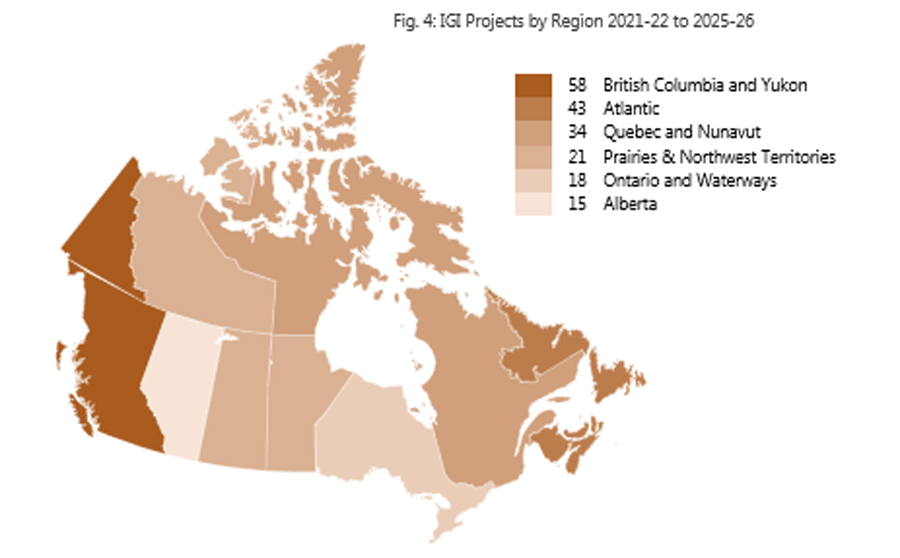

Figure 4 below provides a count of IGI projects (approved as of November 2024) by Parks Canada region. The highest activity levels, in terms of both actual and planned projects, are found in the BC-Yukon and Atlantic regions (58 and 43 projects respectively) while Alberta and the Ontario and Waterways region currently have the least number of projects.

Text description

Figure 4: IGI Projects by Region 2021-22 to 2025-26

Graphic showing the number of IGI projects by region from 2021-22 to 2025-26.

Number of projects by region:

58: British Columbia and Yukon

43: Atlantic

34: Quebec and Nunavut

21: Prairies & Northwest Territories

18: Ontario and Waterways

15: Alberta

Expenditures to date

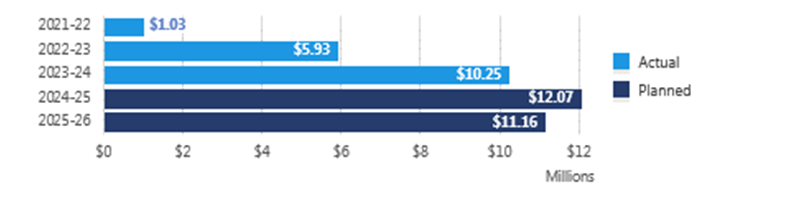

Contributions to Indigenous partners make up the bulk of IGI expenditures since the IGI’s launch in 2021, representing approximately 80% of spending to date. The remaining 20% is composed of wages for Parks Canada staff and related goods and services, such as travel, training, and honoraria. The following analysis focuses on contributions directed towards Indigenous partners for the creation or enhancement of IGPs.

As summarized in Figure 5, a review of financial data identified $40.4 million in planned and actual spending between 2021-22 and 2025-26 supporting projects with Indigenous partners across all of the Initiative’s four phases. Not surprisingly, planned spending is highest in the final two years of the IGI, while actual expenditures were lowest in the IGI’s first year.

Text description

Figure 5: IGI External Approved Projects, Actual and Planned Expenditures, 2021-22 to 2025-26

Bar chart showing the amount of actual and planned expenditures in IGI external approved projects from 2021-22 to 2025-26.

2021-22 (actual): 1.03 million.

2022-23 (actual): $5.93 million.

2023-24 (actual): $10.25 million.

2024-25 (planned): $12.07 million.

2025-26 (planned): $11.16 million.

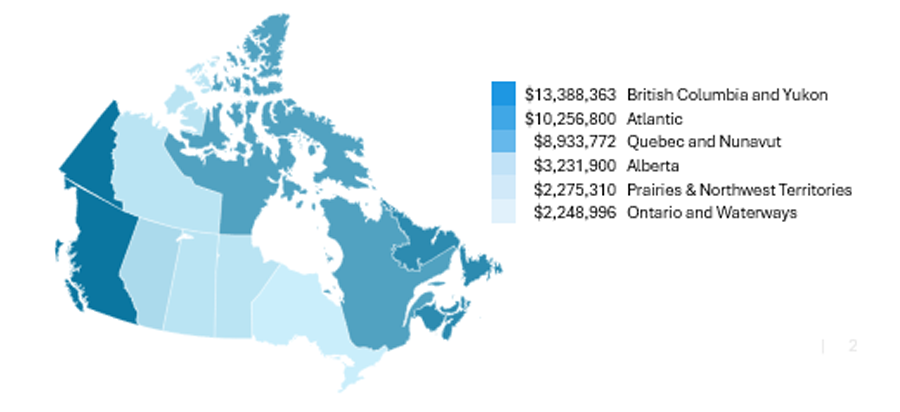

An analysis of these expenditures across Parks Canada’s six regions, as shown in Figure 5, found the highest amounts of planned and actual spending in the BC-Yukon and Atlantic regions, at roughly $13.4 million and $10.3 million, respectively. The lowest approved expenditures were in the Ontario and Waterways region.

Text description

Figure 6: IGI External Approved Projects by Region, Actual and Planned Expenditures, 2021-22 to 2025-26

Graphic showing the amount of planned and actual expenditures for IGI external approved projects by region.

$13,388,363: British Columbia and Yukon.

$10,256,800: Atlantic.

$8,933,772: Quebec and Nunavut.

$3,321,900: Alberta.

$2,275,310: Prairies & Northwest Territories.

$2,248,996: Ontario and Waterways.

Enhanced IGPs

A significant component of the planned and actual expenditures within the BC and Yukon region are related to the enhancement of three long-standing IGPs, i.e. the West Coast Trail (WCT) Guardians, the Broken Group Island Beech Keepers, and the Haida Gwaii Watchmen.

In each case, financial support for these programs had, before the IGI, been drawn from field units’ base-level operational budgets and allocated to partner First Nations through contracts. Under the IGI, the programs received increased funding for their existing operations, as well as funds to invest in assets such as cabins, boats, and equipment, and supports to expand their programs. These are briefly summarized here.

WCT and Beach Keepers

The West Coast Trail (WCT) Guardian Programs are operated by the Huu-ay-aht First Nation, the Ditidaht First Nation, and the Pacheedaht First Nation, whose ancestral homelands fall within the current boundaries of Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. Created in the 1990s (see Figure 1), financial records from 2015-16 to 2020-21 show the WCT programs being supported by contracts totalling roughly $100,000 per Nation.

Records of contribution agreements issued by Pacific Rim National Park Reserve show additional funds being transferred to the WCT Guardian programs starting in 2021-22, supporting operations and the acquisition of additional assets, including cabins for the WCT Guardians.

In 2023-24, three multi-year contribution agreements were approved providing an average of $250,000 per year to each WCT program for activities including trail maintenance, cultural interpretation, environmental and ecosystem monitoring and visitor safety, as well as supports for training and strategic program development. A similar contribution was also approved for the Tseshaht First Nation, which administers the Broken Group Island Beach Keepers program.

In 2022-23, each of the four partner Nations also received a one-year contribution of roughly $100,000 for enhancing the marine components of their programs, linked to the Southern Resident Killer Whale Program.

Haida Gwaii Watchmen

The oldest of the IGPs operating at Parks Canada-administered places, the Haida Gwaii Watchmen program, is administered by the Council of the Haida Nation. Annual contracts supporting the program were first put in place in 1990, for a total of $185,200. In 2010, the contract value was raised to $323,000, followed by another increase in 2020 to $383,000.

While funding was provided via contracts until 2022, contributions from the IGI were initiated in 2021 to strengthen and stabilize the program. This included a contribution of roughly $380,000 for Watchmen salaries, the purchase of additional equipment, and repairs to a Watchmen cabin and another culturally significant site.

This was followed in 2023-24 by a $2.2 million three-year contribution agreement supporting operations and aiming to “improve the long-term sustainability of the program and supports ongoing Haida stewardship, the continuity of Haida culture and is in the spirit of GayG̱ahlda “Changing Tide Agreement.”Footnote 1

Key findings: Relevance

| Expectations | Findings |

| The design of IGPs and the Indigenous Guardians Initiative align with Parks Canada’s commitments to Indigenous Stewardship. | Multiple lines of evidence indicated close alignment between the design of IGPs and the Indigenous Guardians Initiative with Parks Canada’s commitments to Indigenous Stewardship. |

Alignment with Indigenous rights and stewardship

Expectation: The design of IGPs and the Indigenous Guardians Initiative align with Parks Canada’s commitments to Indigenous Stewardship.

Findings: Multiple lines of evidence indicated close alignment between the design of IGPs and the Indigenous Guardians Initiative with Parks Canada’s commitments to Indigenous Stewardship.

Important framing documents for Parks Canada’s work with Indigenous governments and organizations, including and beyond Guardian programs, are the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (UNDA), its 2023-2028 UNDA Action Plan, Parks Canada’s Indigenous Stewardship Framework and Indigenous Stewardship Policy.

Analysis of the alignment between Guardian programs and these framing instruments is in two parts. The first briefly explores high-level alignment between UNDRIP and the impacts of Guardians programs as described in academic literature, while the second considers the structure of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative in relation to the UNDA Action Plan and the Indigenous Stewardship Framework.

UNDRIP and Indigenous Guardians Programs

Indigenous Guardians programs are rooted in long-standing and ongoing work by Indigenous Peoples to reassert jurisdiction over their ancestral territories and fulfill their responsibilities as stewards of their lands, waters, and ice. While the Indigenous Guardians Initiative is a recent development, it fits within this broader movement towards shared governance and Indigenous-led conservation in protected areas, including Parks Canada-administered places.

Research on Indigenous Guardians in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States over the past 15 years (see Annex C: Bibliography). provide evidence of broad alignment between the impacts of these programs and UNDRIP themesFootnote 2, including self-determination, participation in decision-making, cultural and linguistic rights, and environmental protection and conservation.

At the individual level, documented benefits of IGPs include a stronger sense of pride and identity, connection to culture and territory, an increase in income and meaningful employment opportunities, and benefits to physical and mental health.

Community outcomes include benefits to culture and language transmission, preservation of cultural heritage, and a greater sense of intergenerational connection. Case studies from across Canada also provide evidence of environmental benefits, with IGPs contributing more ecological data to support decision-making and monitoring programs reporting positive impacts on species conservation (Popp et al., 2020; EPI, 2022). These findings fit within a wider body of evidence on the environmental benefits of Indigenous-led conservation, based on measures of biodiversity and resistance to both deforestation and environmental degradation (Artelle et al., 2019).

While these findings provide a strong base for asserting the benefits of IGPs to Indigenous human rights and the well-being of Indigenous Peoples, the literature review also identified areas where reports of positive impacts were less conclusive. For example, evidence of the impacts of Guardian programs on self-governance was mixed. While some studies reported increased capacity for self-determination and increased opportunities for collaboration with governments and partners, an assessment of Indigenous community-based monitoring programs, including Guardians and Ranger programs, found that Indigenous participants are still often viewed by governments as “stakeholders” without equal authority (Reed, 2020).

This manifests in governments and funders retaining final decision-making in community-based monitoring programs, a top-down approach described by some researchers as reproducing colonial systems of authority and power (Fache, 2014).

Similarly, while some studies of Indigenous land monitoring programs describe successful integration of Indigenous traditional knowledge, prioritization of Western scientific knowledge was recognized as a common issue. In both Canadian and international contexts, research into collaborative land management found that where differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge frameworks were not meaningfully considered and integrated, Western scientific frameworks were almost always privileged (Preuss & Dixon, 2012).

Lastly, the literature review also identified challenges related to low funding levels and limited access to long-term funding. These were in turn linked to difficulties in programs’ abilities to retain staff and manage workloads as well as organizations’ capacities to plan and execute long-term strategies.

UNDA and the Indigenous Stewardship Framework

Assessment of the IGI’s alignment with the UNDA Action Plan and Parks Canada’s Indigenous Stewardship Framework was based on a review of the Initiative’s structures and processes, including its transfer payment authorities provided through Parks Canada’s General Class Grants and Contributions Program. An analysis of the activities outlined in a sample of contribution agreements funded by the IGI also served to establish links between the IGI and UNDA.

Before discussing the results of this analysis, it is helpful to note that the ISF and the UNDA measures are themselves closely related in themes and goals (see Crosswalk of UNDA and ISF in Annex A); key among them to bring Parks Canada into better alignment with UNDRIP. As such, the five UNDA measures addressed at Parks Canada map to specific elements in the ISF, as demonstrated in Figure 7 on the following page.

IGI program design

While the IGI was developed prior to the ISF’s implementation, document reviews and key informant interviews provided evidence that the Initiative’s design is well aligned with the ISF’s Cultural Continuity and Relationship elements as well as the commitments made to Guardians programs in UNDA Action Plan Measures 35 and 96, which address harvesting rights and on-the-land learning initiatives via enhanced and sustainable IGPs (see Legal and policy frameworks).

Relationship elements are reflected in the IGI’s partner-led approach, which requires collaborative development in accordance with partners’ values and priorities, as well as the IGI funding tools, which conform to the Directive on Transfer Payments Appendix K: Transfer Payments to Indigenous Recipients, which provide flexible and administratively lighter processes meant to promote stable relationships with partners.

The IGI’s design also touches upon Governance and Economic Opportunities. Implemented IGPs are managed by Indigenous partners, with capacity building and other supports provided by Parks Canada relative to needs.

IGI funded programs

While the IGI was not designed to prescribe stewardship activities to Indigenous partners, a review of contribution agreements found that objectives and activities were nonetheless well aligned with the ISF and UNDA.

Most IGP goals focused on the protection and conservation of natural and/or cultural heritage, as well as the integration of Indigenous knowledge and perspectives within the stewardship of Parks Canada-administered sites. While activities varied widely, the most common types were wildlife or species at risk management, ecological or cultural site monitoring, and environmental restoration.

Many IGP agreements also reflected one or more of the UNDA measures (see Annex A). Examples include programs seeking to increase the involvement of Guardians in park management, to involve youth in learning and career development activities, or to conduct ceremonial harvests in Parks Canada-administered places.

Text description

Figure 7: Indigenous Stewardship Framework and Parks Canada’s UNDA Measures

Visual summary of alignment between the Indigenous Stewardship Framework and Parks Canada's UNDA Measures.

A central ring of enabling elements carries the words Education and Understanding, Acknowledgements and Relationships. Another ring surrounds the first one and carries the words Indigenous Knowledge Systems, Shared Governance, Practices on the Land, Water, and Ice, and Economic Opportunities.

From the outer ring labeled Shared Governance, a text box reads Measure 95 Governance.

From the outer ring Indigenous Knowledge Systems, a text box reads Measure 97 Indigenous Knowledge.

From the outer ring Cultural Continuity, two text boxes read Measure 35 Harvesting and Measure 96 Cultural Continuity.

From the inner ring Acknowledgments, a text box reads Measure 110 Acknowledgments and Apologies.

Current and future challenges

While alignments between the design of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative and Parks Canada’s commitments to Indigenous Stewardship were largely evident, key informant interviews with Parks Canada staff and management, all of whom supported the IGI’s approach, did identify challenges stemming from areas in which rules or practices have not integrated Indigenous laws, customs, or needs.

For example, staff from the Centre of Expertise on Grants and Contributions noted that while the new transfer payment options for Indigenous recipients (see “Financial tools to support healthy and respectful relationships”) have been positively received, some Parks Canada staff reported concerns on behalf of Indigenous partners related to clauses stating that disagreements over contribution agreements will be settled in Canadian courts.

Requests by the GCGCP to modify these clauses were not granted, however Centre of Expertise on Grants and Contributions staff shared that in some instances the clauses were simply omitted from agreements (rather than being modified) as they were not required to ensure that arguments would be resolved in provincial courts under Canadian law.

Looking ahead, Parks Canada senior management also noted that, should Indigenous Guardians programs continue to expand, they will likely raise complex questions surrounding labour relations, employment opportunities, and equitable pay. In areas where Guardians take on responsibilities that are similar or the same as those of current park employees, such as environmental monitoring, compliance, or interpretation, grey areas emerge in terms of comparable pay rates, occupational health and safety considerations, access to staff housing, and identification systems, such as uniforms.

Finally, while UNDA Measure 96 Cultural Continuity commits Parks Canada to implement “enhanced and sustainable” Guardian programs, the IGI remains a temporary initiative, supported by external funding which is currently set to end in 2025-26.

Key findings

Overall, it was found that there is a close alignment of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative with the Indigenous Stewardship Framework, and the UNDA Action Plan, with all three sharing high-level goals of honouring Indigenous human rights and facilitating the implementation of UNDRIP.

The IGI’s program design was found to reflect multiple elements from the Indigenous Stewardship Framework, while a review of IGI contribution agreements identified clear links between project objectives and the five UNDA Action Plan Measures.

Areas of reported misalignment or concern included some of the legal framing of contribution agreements, the potential for questions around compensation for comparable roles, and the provision of sustainable funding, which is explored further in this report (see Sustainability section).

Key findings: Relationships

| Expectations | Findings |

| Parks Canada-supported IGPs contribute to the development of positive relationships between field units and Indigenous governments and organizations. | A review of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative’s structures found them to be in alignment with relationship-building principles outlined in the Indigenous Stewardship Framework. Opportunities to enhance the cultural responsiveness of funding instruments were also identified. |

Healthy and respectful relationships

Expectation: Parks Canada-supported IGPs contribute to the development of positive relationships between field units and Indigenous governments and organizations.

A review of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative’s structures found them to be in alignment with relationship-building principles outlined in the Indigenous Stewardship Framework.

Opportunities to enhance the cultural responsiveness of funding instruments were also identified.

Lines of evidence used to explore how Parks Canada’s approach to Indigenous Guardians programs can support respectful relationships with Indigenous partners included document reviews, key informant interviews, and an analysis of funding mechanisms and recent contribution agreements. Findings from the most recent evaluation of Parks Canada’s General Class Contribution Program also provide additional context.

Healthy relationships

The concept of healthy and respectful relationships used for this evaluation is drawn from Parks Canada’s Indigenous Stewardship Framework (ISF) and Indigenous Stewardship Policy. Within these, relationships are described as an enabling element, meaning a set of practices that help create the necessary conditions for success in other areas.

Positive contributions to relationships are framed as commitments to support Indigenous Peoples in fulfilling their stewardship responsibilities by respecting Indigenous laws and by acknowledging the different capacities and interests of Indigenous governments, i.e., “meeting them where they are and where they are going”. This extends to ensuring that capacity building is supported where appropriate and as requested. Recognizing that colonial legacies have in some places eroded Indigenous systems and protocols for engaging with other communities, contributing to complex relationships between Indigenous governments, the Indigenous Stewardship Policy also commits Parks Canada to inviting open dialogue about stewardship responsibilities.

Perspectives on relationships

Across all key informant interviews, relationships were seen as central to the Indigenous Guardians Initiative, whether as a means of creating strong, locally relevant programs, or as a key outcome of the development process itself. In that sense, Guardians programs were often described as catalysts, capable of creating wider meaningful changes in the dynamics between Parks Canada and Indigenous communities.

Analysis of interviews with staff who support Guardians programs found that two aspects of the IGI were consistently described as critical to forming healthy and respectful relationships with Indigenous partners: partners’ ability to pursue their own priorities and Parks Canada’s ability to offer flexible funding.

Partner priorities

A file review exploring contribution agreements signed under the IGI provided a window into how Indigenous governments and organizations determined their community needs and interests.

Though exact processes varied, the file review found that community engagement was the norm. Documented mechanisms ranged from community-based, participatory goal-setting, such as community engagement sessions planned by the Batoche National Historic Site Guardians program, to formal co-development processes between governments and advisory boards, such as the Torngat Mountains Guardians program, which was developed through collaborative meetings between the Makivvik Corporation, the Nunatsiavut Government, and the Cooperative Management Board for Torngat Mountains National Park.

Some contribution agreements also linked program goals to shared governance agreements between Indigenous Nations and the Government of Canada. Examples include the Haida Gwaii Watchmen agreement which aligned its aims with the GayGahlda | Kwal.hlahl.dayaa Changing Tide Reconciliation Framework Agreement, signed by the Haida Nation, the Government of Canada, and the Government of British Columbia, and the contribution for the Nah?a Dehe K’ehodi Guardians which cited the Ndahecho Gondié Gháádé cooperative management agreement for Nahanni National Park Reserve.

Program objectives and activities outlined in the contribution agreements also varied considerably, which aligns well with the idea of local Indigenous governments being encouraged to pursue their own priorities. That said, broad patterns did emerge while reviewing IGI agreements. Most IGPs reflect interests in monitoring and conservation activities, whether at ecological or cultural sites, as well as in as integrating Indigenous traditional knowledge within the stewardship of Parks Canada administered sites.

Communicating clearly

From the perspective of creating and/or maintaining positive relationships with Indigenous partners, both IGI Regional Coordinators and field unit management noted communication challenges within Parks Canada and with its partners and surrounding communities. This was most often noted in environments in which multiple Indigenous communities hold ties to what are now Parks Canada-administered places and/or where multiple federal departments have ongoing partnerships with the same groups.

Issues raised included the need to address confusion between the Indigenous Guardians programs supported by Parks Canada and those of other federal government departments, either currently or in the past. In some cases, negative experiences in the past led field units to avoid using the term ‘Guardians’, to separate Parks Canada’s activities from those previous attempts.

In regions where relationships between Indigenous governments were complex or sometimes strained, field unit management reported paying close attention to information shared about new or enhanced Guardian programs, including in the media, through advisory committees, and through informal channels. Concerns included confusion over roles, resources being made available to different groups, and forms of access being granted for activities such as harvesting. One key informant described this as ensuring equity of information among regional partners.

In a similar vein, Regional Guardians Coordinators and field unit staff also described making efforts to clarify the IGI’s aims to Parks Canada staff to mitigate misperceptions over program goals and where funds could be directed.

This was felt to reflect the difference between Guardians programs and other initiatives based on temporary supplemental funding, which typically leverage resources and partnerships to directly further Parks Canada objectives. While Guardians programs have been initiated based on ideas from field units or from staff working in the Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation Directorate, bringing clarity to the partner-led nature of the IGI was important in the early stages of its implementation.

Financial tools to support healthy and respectful relationships

Prior to 2021, long-standing Indigenous Guardians programs, including the Haida Gwaii Watchmen, the West Coast Trail Guardians, and the Broken Group Island Beach Keepers were primarily funded via contracts with Parks Canada. Other engagements, such as consultations tied to new protected areas, typically relied on standard contribution agreements.

In 2022, new funding authorities were implemented by Parks Canada, allowing access to grants, micro-grants, and three new types of contributions for Indigenous recipients via the General Class Grants and Contributions Program (GCGCP). Since that time, the IGI has employed these new authorities to support Indigenous partners, typically by first transferring funds to field units, who then work with staff from the Centre of Expertise on Grants and Contributions to develop the agreements.

Each of the options available to the IGI are described in more detail in Annex B: Transfer payments to Indigenous recipients. Key difference between standard contribution agreements and those designed for work with Indigenous partners include the ability to retain or redirect unspent funds, in the case of fixed or flexible agreements, or to move funds between projects, in the case of block contributions. All three types of agreements also feature lighter administrative and reporting requirements.

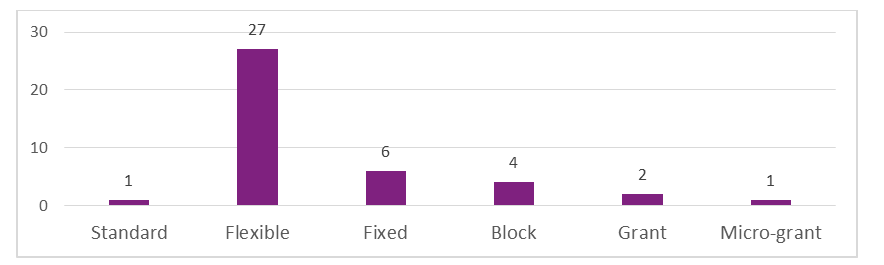

As summarized in Figure 8 below, a review of a sample of IGI agreements found that since 2022 most Indigenous Guardians programs have been supported through flexible contribution agreements. Fixed and block contributions, though less common, are also employed, while standard contribution agreements, grants, and micro-grants were least used.

Impacts of funding tools

The potential for funding mechanisms to support or detract from relationships with Indigenous partners was highlighted in the 2022 evaluation of Parks Canada’s General Class Contribution Program, since renamed the General Class Grants and Contribution Program.

As the new authorities were not yet available, the evaluation explored the use of standard CAs. Evaluation findings identified several challenges which were felt to undermine relationship-building with Indigenous partners, as reported by both partners and Parks Canada staff.

Key among these challenges were the GCCP’s inflexible payment structures, the workload generated by monitoring and reporting requirements, and the level of overall scrutiny experienced by partners.

In a case study conducted for the GCCP evaluation, staff working for an Inuit Regional Organization reported that barriers to adjusting workplans and timelines as set down in standard CAs signaled a limited recognition on the part of Parks Canada of the needs, capacities, and practical realities of Indigenous organizations, many of which operate in remote locations and are structured to support traditional practices, rather than being modeled after federal or provincial governments.

Recent interviews with Parks Canada staff supporting long-running programs such as the Haida Gwaii Watchmen or West Coast Trail Guardians, identified similar challenges with the use of contracts, which were the main mechanism for funding both programs until 2021.

In each case, contracts were felt to have fostered unequal dynamics with partner First Nations as well as perception of their stewardship activities as tasks or services rendered to Parks Canada. The use of financial tools like task authorization forms were also felt to limit partners’ autonomy and ability to evolve their programs relative to their local priorities and interests.

Text description

Figure 8: Sample of Indigenous Guardians Initiative Funding Agreements by Type (2022-2024)

This figure shows a bar chart outlining the number of IGI agreements, by type, included in the sample of contribution agreements reviewed as part of the evaluation.

The number of agreements is:

Standard: 1.

Flexible: 27.

Fixed: 6.

Block: 4.

Grant: 2.

Micro-grant: 1.

Findings from key informant interviews indicate that the addition of the new agreement types, as well as grants and micro-grants, lessened the issues noted above. While still requiring descriptions of goals and activities, it was noted that the language used in contribution agreements is less prescriptive and more readily adapted to suit local contexts, allowing greater decision-making power on the part of recipients.

A review of monitoring and reporting requirements in IGI agreements support this, in that several examples of modified language were found specifying how performance measurement, monitoring, and reporting would be approached by partners. Identified in roughly one third of the reviewed agreements, modifications included:

- Providing funding specifically for reporting and monitoring activities;

- Establishing monthly working meetings between local program coordinators and Parks Canada staff;

- Ensuring Guardians staff on-the-land are aware of the outcomes and indicators in the funding agreement, so they can accurately monitor and evaluate them; and,

- Holding meetings and learning sessions to establish clear roles and responsibilities between Parks Canada staff, Guardians coordinators, and/or Indigenous governments.

Other modifications identified in contribution agreements set out expectations for Parks Canada’s reporting to Indigenous organizations. This included requirements for sharing project progress with community members as well as guidelines for sharing and using reported data in accordance with cultural protocols surrounding traditional knowledge and intellectual property.

Culturally appropriate practices

While fixed, flexible, and block CAs have provided clear benefits to building and maintaining positive relationships with Indigenous partners, both field unit staff and members of the grants and contribution team identified remaining challenges, with some key informants expressing concern and discomfort due to their awareness of how certain practices were poorly aligned with Indigenous cultural or community norms.

In one example, field unit staff reported a lack of appropriate mechanisms for compensating individuals, particularly Elders, for their contributions to Guardians programs. While micro-grants provide a partial solution, as they feature a simplified authorization process for payments under $5,000, Indigenous individuals must still provide personal information, banking details in particular, to government authorities to receive compensation, which Centre of Expertise on Grants and Contributions staff noted was often under $500.

While relevant to the IGI, Centre of Expertise on Grants and Contributions staff also noted that this issue is not limited to Indigenous Guardians programs. Interviews with Parks Canada staff confirmed that efforts are being made to address this more widespread challenge via a Respectful Payments initiative.

In another instance, staff reported difficulties with the terms of the risk assessments which are required for all types of CAs. Risk management tools were built into Parks Canada’s contributions program in 2018-19 as a means of aligning reporting requirements and selection criteria with project risk levels. This approach was retained when Parks Canada added contributions for Indigenous recipients to its transfer payment authorities in 2021, with capacity and risk levels established through a standard Transfer Payment Wizard tool. Based on these, flexible and block agreements are designated for Indigenous recipients assessed as higher capacity, while grants and micro-grants are reserved for projects with a low overall risk assessment.

Interview participants reported discomfort in completing the risk assessment template, expressing concern over using their knowledge of Indigenous governments, which in smaller communities are likely to derive from personal or even familial ties, to generate risk scores. Key informants also reported concerns with assessment criteria linking the percentage of funding coming from a single source to project risk levels, as most Indigenous Guardians programs are 100% funded by Parks Canada.

In response to this requirement, key informants stated that: “(…) this characterization does not accurately reflect our working relationship with (name) First Nation. While Parks Canada frequently acts as the primary contributor to programs in partnership with First Nations, this approach is an essential part of our commitment to reconciliation and to supporting Indigenous stewardship under UNDA automatically categorizing these partnerships as high risk may inadvertently imply a dependency on government support and overlook the opportunities for economic development that are integral to these collaborations. This can create an unintended perception that First Nation partners are being unfairly penalized, which is contrary to the spirit of collaboration and mutual growth that we aim to foster.”

These concerns echo findings from a 2021 review by Parks Canada internal auditors of the risk analysis instruments supporting contribution agreements. Review results highlighted questions over the instruments’ ability to appropriately assess the financial and management capacities of Indigenous organizations, noting that the risk factors and scoring instructions where the same as those applied to very different organizations, such as universities and provincial governments.

Key findings

Overall, findings support the conclusion that the Indigenous Guardians Initiative has been structured to support healthy and respectful relationships as described in Parks Canada’s Indigenous Stewardship Framework and Indigenous Stewardship Policy. There was near consensus among key informants that IGPs established with Indigenous governments, based in community priorities, and supported by flexible funding tools, can be the basis for even richer collaborations over time.

Key informant interviews, supported by document reviews, also identified some challenges and complexities. Field unit staff and management noted the importance of maintaining clear communications with all partners and ensuring that information about the IGI is shared with all interested parties. Similarly, Indigenous Guardians Coordinators noted the importance of ensuring that the aims of the IGI were well understood internally by Parks Canada staff.

Finally, challenges were identified with specific financial processes and practices provided to the IGI through the GCGCP, which, despite the much-improved flexibilities of contribution agreements for Indigenous recipients, were not yet adaptable to Indigenous cultural norms. These included means of appropriately compensating individuals, Elders in particular, for their contributions to projects and means of considering project risks that are better suited to the nature of Indigenous Guardians programs and Parks Canada’s commitments to supporting Indigenous stewardship.

Key findings: Effectiveness

| Expectations | Findings |

| Organizational and governance models developed for the IGI are effective in facilitating the implementation of Indigenous Guardians programs. | While the newness of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative and its financial instruments created some challenges and lessons learned, evidence indicates that the IGI has been effective in supporting the development of Indigenous Guardians programs. |

Effective processes and supports

Expectation: Organizational and governance models developed for the IGI are effective in facilitating the implementation of Indigenous Guardians programs.

While the newness of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative and its financial instruments created some challenges and lessons learned, evidence indicates that the IGI has been effective in supporting the development of Indigenous Guardians programs.

Lines of evidence used to assess the effectiveness of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative at supporting the development and implementation of Guardians programs included document reviews, key informant interviews, a survey of field unit staff, and an analysis of recent contribution agreements.

Program structures and governance

Interviews and surveys with Parks Canada staff, ranging from field unit staff to senior management, identified broad agreement on both the strengths and the challenges of the IGI. Most consistent was the view that the flexible and partner-led approach taken by the Initiative, which has been explored in the previous sections of this report, was essential to the IGI’s ability to meet its goals.

From an administrative point of view, most interview participants also felt that the IGI’s application and approval process was appropriate and simple, at least in comparison to other funding programs, and met the need to be agile and adaptable to varying local circumstances. Funding tools were also seen by staff as more effective than previously available instruments, i.e., contracts and standard contribution agreements, with lessened reporting requirements and a greater ability to move funds if needed.

Interviews and a staff survey also found a high degree of consensus about the effectiveness of locating the IGI’s staff and governance within the Operations Directorate (see Figure 3 above). Respondents pointed to the signing authority for transfer payments being set at the Senior Vice-President level as helpful in getting programs approved in a timelier manner. Senior staff within field units and the national office also felt that placing the IGI within Operations had allowed for experimentation and calculated risk-taking, which in turn helped their teams learn what works and how best to adapt their approaches to suit local contexts.

The six Executive Director Offices were also felt to be a good location for the National and Regional Indigenous Guardians Coordinators, in that the EDOs already performed a bridging function among a region’s field units, and between the field and national office directorates, which aligned well with coordinators’ responsibilities.

Lastly, the main strengths of the Guardians Coordinators, as described by other key informants, were their roles as advisors, listeners, and convenors, capable of supporting discussions with various Indigenous communities and organizations, assisting with proposals, responding to questions from field unit staff and adapting their activities to the differing needs of their regions.

Initiative goals and targets

The partner-led nature of the Indigenous Guardians Initiative means that outcomes of individual programs are expected to reflect local priorities.

As a result, IGI key results were not narrowly defined, beyond setting a target for the number of programs created. Six initiative-level goals were instead oriented towards promoting awareness, supporting collaboration, and creating conditions for success.

As the Indigenous Guardians Initiative is still within its five-year period, the following provides a snapshot of the progress made to date against five of the goals, followed by an overview of reported challenges and lessons learned. The sixth goal, program sustainability, is addressed in the final section of this report.

Indigenous Guardians Initiative 2021-2026 Goals:

- Collaborating with Indigenous partners to support new Indigenous Guardians programs at Parks Canada-administered places;

- Funding 35 or more Indigenous Guardians programs between 2022-2026;

- Increasing awareness and capacity for Guardians programs at Parks Canada-administered places;

- Telling the story of Guardians, internally and externally;

- Sharing best practices and connecting Indigenous Guardians programs; and,

- Moving the created and enhanced programs towards sustainability.

Collaborations to support new Indigenous Guardians programs at Parks Canada-administered places

As noted in the Relationships portion of this report, interview data and a review of contribution agreements provided evidence that IGPs were built collaboratively with Indigenous partners.

A review of contribution agreements found that most of the programs created under the IGI focused on the protection and conservation of natural and cultural heritage places, as well as the integration of Indigenous traditional knowledge and perspectives within the stewardship of Parks Canada-administered sites.

Funding 35 or more Indigenous Guardians programs between 2022-2026.

As of September 2024, 37 IGPs were operating at Parks Canada-administered places with an additional five programs in the capacity building phase. Seven exploratory initiatives were ongoing.

Increasing awareness and capacity for Guardians programs at Parks Canada-administered places.

Within Parks Canada, the Regional Guardians Coordinators are tasked with building awareness of IGPs and supporting field units as part of the Executive Director Office teams. This includes providing advice and information on regional issues to field units, reviewing IGP proposals, and supporting the development of contribution agreements.

Key informant interviews and results from the field unit staff survey indicate that the additional capacity provided by Regional Coordinators, particularly but not exclusively those without Indigenous liaison positions, contributed significantly to the development of IGPs. Without these, most survey respondents felt that field unit resources were not sufficient to effectively support IGP development.

Telling the story of Guardians, internally and externally.

Stories from Indigenous partners about their experiences belong to partners and can only be shared with their support.

IGI staff reported that they are developing a storytelling initiative, in which Indigenous partners can request funds to produce videos or images related to IGPs. Funds will be directed at employing community members as well as purchasing equipment. As of September 2024, the IGI has funded one video proposal, and received expressions of interest from a few additional partners. The story initiative will be on-going for 2025-26.

Sharing best practices and connecting Indigenous Guardians programs.

Within Parks Canada, information related to IGPs, including resources, opportunities for collaborations, and clarifications of internal processes, is circulated by the Regional Guardians Coordinators, who lead and/or contribute to regional Indigenous Relations networks. The Regional Coordinators also hold their own weekly meetings to discuss developments and challenges, as well as policy application.

In addition, the review of contribution agreements found that roughly one-quarter of all funding agreements (10 of 41) included in the sample featured networking and liaising with other Guardians programs as an activity supporting program development.

Five of these agreements were from communities in British Columbia and Yukon region, i.e., the Tseshaht Beach Keepers, the Huu-ay-aht West Coast Trail Guardians, the Osoyoos Indian Band Guardians, the Lower Similkameen Indian Band and the Kluane Land Guardian Initiative. This may reflect the existence of many long-established Guardians programs within this region, which could serve as potential resources for newer programs.

Lessons and learning curves

Challenges experienced in developing and supporting the implementation of Indigenous Guardians Programs were often framed as being the result of applying newer approaches (such as the partner-led model) and using new financial tools.

Centre of Expertise on Grants and Contributions staff who supported the preparation of flexible contribution agreements reported early challenges in clarifying to staff how the transfer of unspent funds from advance payments was intended to function. While flexible agreements allow remaining funds at fiscal year-end to be carried forward without reworking budgets, this administrative streamlining is lessened when agreements are signed late in the fiscal year, causing advance payments to be requested when it is less likely that work will be completed. Partners may then be asked to justify how those amounts will be spent over a short period.

Other practical challenges reported by key informants included timing program approvals so as not to miss the short operational seasons in the north, finding housing for Guardians, providing access to keys, equipment, or workspaces and finding solutions to questions relating to insurance and occupational health and safety (OHS) regulations. OHS questions also emerged in some of the long-established Guardians programs, as their transition from contracts to contribution agreements created a need for clarification around responsibilities and liabilities.

Field unit staff also noted that while administrative burdens were mitigated by the IGI’s flexibilities and the new GCGCP tools, reporting requirements and application processes could still be challenging, depending on the capacity levels of partners’ governing bodies. Delays in starting programs were also reported due to the need for more discussion and for providing more clarity to multiple partners or stakeholders.

Lastly, due to the partner-led nature of the process, some senior staff within field units reported being surprised by the priorities of Indigenous partners, requiring readjustment of their expectations and plans for what supports the field unit would need to provide.

Key findings

A review of program results found that the IGI is on track to meet the five stated goals listed above. Key informant interviews, supported by evidence from the survey of field unit staff, indicate that program structures were considered appropriate and effective by internal Parks Canada stakeholders, while still noting some logistical and procedural challenges to the implementation of new or enhanced Guardians programs.

Key findings: Sustainability

| Expectations | Findings |

| Strategies are in development to sustain Indigenous Guardians programs and to mitigate the risks to both Parks Canada and program partners. | While the review of contribution agreements and key informant interviews identified some planning at the local level to mitigate risks and/or sustain the Indigenous Guardians programs, there was limited evidence of a broader Parks Canada strategy to support IGPs over the long term. |

Planning for sustainability

Expectation: Strategies are in development to sustain Indigenous Guardians programs and to mitigate the risks to both Parks Canada and program partners.

While the review of contribution agreements and key informant interviews identified some planning at the local level to mitigate risks and/or sustain the Indigenous Guardians programs, there was limited evidence of a broader Parks Canada strategy to support IGPs over the long term.

Lines of evidence used to consider the sustainability of the Indigenous Guardians programs included a review of recent and planned expenditures, analysis of contribution agreements, and results from a literature review, key informant interviews, and a survey of field unit staff.

Identifying risks and impacts

A review of literature on Indigenous Guardians programs found that while funding models and mechanisms differed across regional and national contexts, difficulties securing long-term commitments were reported in multiple studies of Canadian and international programs (North Sage Research, 2022; Hunt, 2012). Impacts of precarious funding on Guardians programs identified in the literature review included challenges retaining staff, missed training opportunities, increased time spent away from operations to seek funding, and limited capacities to plan and execute long-term strategies (Gibson & Ford, 2023). Some studies also found that the issues listed above compound barriers to finding stable funding, as applicants struggle to demonstrate sufficient internal capacity (Peachy, 2015).

Interviews and surveys with Parks Canada staff and senior managers noted similar concerns for their respective Indigenous partners, while also outlining risks and potential negative impacts to Parks Canada. The latter fell into three broad categories: staff morale, missed opportunities, and organizational impacts, primarily but not limited to damaging relationships with Indigenous partners.

Risks to staff morale were linked to the temporary nature of programs supported by time-limited funds, which are often staffed using term positions, leading to the potential loss of colleagues once funding ends. More specific to relationship-based programs like the IGI, it was also noted that it can be disheartening to see how the end of funding impacts partners and community members with whom Parks Canada staff have formed connections and/or established trust.

Concerns over missed opportunities spoke to the anticipated impacts of a network of vibrant IGPs working alongside Parks Canada and contributing to shared interests. Anticipated short-to-mid term benefits to Parks Canada were often linked to the idea of more staff holding working-level relationships with Indigenous partners, which could in turn foster more understanding between the organizations and more chances to collaborate on projects when opportunities arise.

Longer-term expectations focused on the fulsome return of Indigenous conservation to the lands, waters, and ice Parks Canada administer, furthering UNDRIP-related goals and offering enduring benefits to both parties in terms of economic opportunities, efficiency gains, new ways of working, and better ecological outcomes.

While these benefits are speculative, literature review findings do indicate that Indigenous-led conservation has measurable positive impacts on biodiversity and the health of ecosystems, and that IGPs in particular contribute to a greater knowledge base of ecological data to support decision-making (see “Alignment with Indigenous rights and stewardship”).

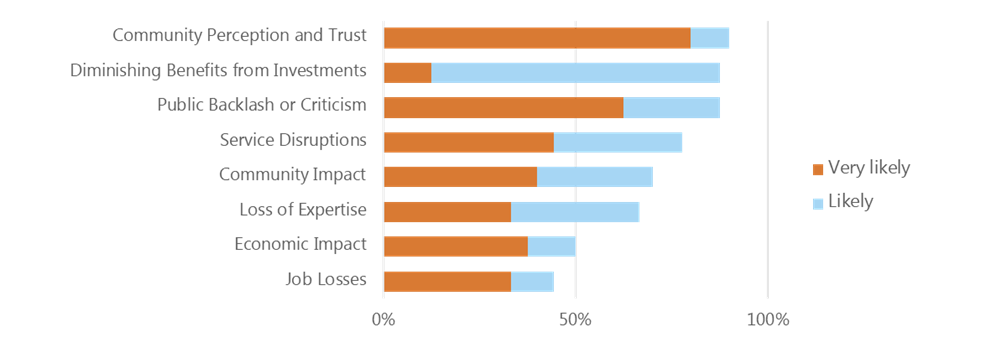

Finally, organization-level impacts group together a range of risks typically associated with funding cuts. These were primarily drawn from a literature scan and incorporated into a survey of field unit staff who support new or long-standing Guardians programs.

Eight impact types were described, and survey participants were asked to rate the likelihood of each occurring should supports to Indigenous Guardians programs cease.

These risks were:

- Damage to community perception and trust, impacting Parks Canada’s credibility;

- Diminished benefits from investments in research, infrastructure, or institutional knowledge that may not easily be recovered;

- Loss of expertise from specialized knowledge and skills among staff, which may be challenging to replace;

- Job losses among program staff, leading to unemployment and economic impacts;

- Economic impacts in the form of disruption to local economies if funding cuts lead to reduced spending or employment in related sectors

- Reduction in community resources related to the program(s), potentially leading to increased strain on local governments or organizations;

- Service disruptions, losses or reductions in the benefits provided by the program, such as environmental monitoring or other activities of mutual interest;

- Negative political consequences, including public backlash or criticism.

An overview of survey participants’ responses is provided on the next page.

Figure 9 below provides an overview of the proportion of respondents who indicated an impact was either likely or very likely should funding cease.

While each of the listed potential impacts was regarded as somewhat likely by field unit staff, damage to community perception and trust was seen as the most probable, with 80% of respondents finding it “very likely”, followed by 10% finding it “likely”.

Most survey participants also expressed concern for public backlash or criticism of Parks Canada, with 60% rating it as “very likely”, as well as diminishing benefits of the investments made through the IGI in areas like purchased assets and institutional knowledge, 75% rating this as “likely”.

Comments accompanying the rating questions reinforced that the main foreseeable consequence of ceasing financial supports to IGPs, particularly in regions with few to no existing Guardians programs and limited previous engagement with Indigenous communities, would be damage to the newly built trust and budding relationships between Indigenous partners and Parks Canada teams.

Staff from field units with longer established relationships with Indigenous partners were more likely to describe impacts from the end of funding as a regression to the previous status quo. From a financial perspective this would mean a return to the previous model in which field units supported IGPs using their own baseline resources, which would almost certainly fall well below the funding levels achieved through the IGI and require cuts to expenditures in other areas. From a relationship perspective, field unit staff felt that the end of funding would be perceived by partners as a considerable disappointment, as the Initiative’s design and resources had raised expectations for the future, despite the time-limited nature of the IGI having been made clear.

Text description

Figure 9: Rating of the Likelihood of Impacts Related to the End of IGI Funding

The figure presents the proportion of interview respondents who indicated an impact was either likely or very likely should funding to the IGI cease.

In order of perceived likelihood, it reads:

Community Perception and Trust

Diminishing Benefits from Investments

Public Backlash or Criticism

Service Disruptions

Community Impact

Loss of Expertise

Economic Impact

Job Losses

Planning and mitigation

Key informant interviews, with Parks Canada staff, document reviews, and a file review of funding agreements linked to the Indigenous Guardians Initiative found evidence of some efforts to mitigate the risks described above on a program-by-program basis but did not identify broader strategies to prioritize IGPs by providing funding or other supports beyond the end of the IGI’s five-year commitments in 2026.

Approaches identified in funding proposals and grant requests to help secure ongoing funds or create more resilient programs included support for training activities and skill development, funding for new assets and equipment, and, in a few cases, funding for program staff to seek out new partners and resources.

Training and skill development activities were described as helpful to programs looking to pass on necessary knowledge from season to season, as well as promoting workforce retention where there may be few available candidates.

Acquisition of assets, such as boats or safety equipment, were also seen as investments into programs, helping them to ensure safe operations over the next several years.

Specific to seeking out new funding sources, the file review noted one grant supporting work to identify possible new donors and/or strategic partnerships, such as preparing proposals and creating future workplans.

Another grant was identified supporting exploratory conversations with other federal agencies, including Canadian Heritage and Indigenous Services Canada, to consider possibilities of interdepartmental support.