Multi-species Action Plan for Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site of Canada and National Historic Sites administered by Parks Canada in Mainland Nova Scotia

PROPOSED

Species at Risk Act

Action Plan Series

2025

Long description for cover image

The cover page is a series of seven photos arranged in clockwise order from the top left: Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii), photo credit: Jeffie McNeil; Petroglyph, photo credit: Parks Canada; Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus melodus), photo credit: A. DiMarco; Wisqoq (Fraxinus nigra), photo credit: Cody Chapman; Eastern Ribbonsnake (Thamnophis sauritus), photo credit: Wesley Pitts; Canoe, photo credit: Eric Le Bel; Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica), photo credit: Jennifer Eaton.

On this page

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Executive Summary

- 1. Context

- 2. Site-based population and distribution objectives

- 3. Conservation and recovery measures

- 4. Critical habitat

- 5. Evaluation of socio-economic costs and of benefits

- 6. Measuring progress

- 7. References

- Appendix A: Species information, objectives and monitoring plans for KNPNHS and NHSs of Mainland NS

- Appendix B: Conservation and recovery measures that will be implemented

- Appendix C: Other conservation and recovery measures that will be encouraged through partnerships or when additional resources become available

Document information

Recommended citation:

Parks Canada. 2025. Multi-species Action Plan for Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site of Canada and National Historic Sites administered by Parks Canada in Mainland Nova Scotia. Species at Risk Act Action Plan Series. Parks Canada, Ottawa. vii + 53 pp.

Official version

The official version of the recovery documents is the one published in PDF. All hyperlinks were valid as of date of publication.

Non-official version

The non-official version of the recovery documents is published in HTML format and all hyperlinks were valid as of date of publication.

For copies of the action plan, or for additional information on species at risk, including Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, recovery strategies, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species At Risk Public Registry Footnote 1.

Cover illustrations (clockwise from top left): Blanding’s Turtle, photo credit: Jeffie McNeil; Petroglyph, photo credit: Parks Canada; Piping Plover, photo credit: A. DiMarco; Wisqoq, photo credit: Cody Chapman; Eastern Ribbonsnake, photo credit: Wesley Pitts; Canoe, photo credit: Eric Le Bel; Barn Swallow, photo credit: Jennifer Eaton.

French title:

Plan d’action multi-espèces pour le parc national et le lieu historique national du Canada Kejimkujik ainsi que pour les lieux historiques nationaux administrés par Parcs Canada dans la partie continentale de la Nouvelle-Écosse.

© His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister responsible for Parks Canada, 2025. All rights reserved.

ISBN to come

Catalogue no. to come

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Preface

The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) Footnote 2 agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. The Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA) was enacted to protect wildlife species at risk in Canada and to complement other legislation in conserving Canada’s biodiversity. Today, SARA is a key contributor Canada’s 2030 Nature Strategy – Halting and Reversing Biodiversity Loss in Canada, which charts a path for how Canada will implement the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Under SARA, the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of action plans for species listed as Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened for which recovery has been deemed feasible. They are also required to report on progress five years after the publication of action plans on the Species at Risk Public Registry. Under SARA, action plans provide the detailed recovery planning that supports the strategic direction set out in recovery strategies. They outline what needs to be done to achieve the population and distribution objectives identified in recovery strategies, including the measures to be taken to address the threats, the monitoring of the recovery of the species, as well as the proposed measures to protect critical habitat identified for the species. Action plans also include an evaluation of the socio-economic costs of the plan and the benefits to be derived from its implementation. Action plans are considered one in a series of documents that are linked and should be taken into consideration together, including COSEWIC status reports, recovery strategies, and other action plans produced for the species.

The Minister responsible for Parks Canada Agency is the competent minister under SARA for species found in Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site and Mainland Nova Scotia National Historic Sites of Canada and has prepared this action plan to implement recovery strategies that apply to the park and historic sites as per section 47 of SARA. It has been prepared in cooperation with Kwilmu’kw Maw-klusuaqn, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), and the Province of Nova Scotia as per section 48(1) of SARA.

Success in the recovery of these species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies and will not be achieved by Parks Canada or any other jurisdiction alone. All Canadians are invited to join in supporting and implementing this action plan for the benefit of multiple species and Canadian society as a whole.

Implementation of this action plan is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints of Parks Canada and participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Acknowledgments

Parks Canada would like to acknowledge those who have contributed to the development of this action plan.

We begin by acknowledging that Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site, as well as the other National Historic Sites within this plan, are located on unceded Mi’kmaq territory. Mi’kma’ki, the ancestral homeland of the Mi’kmaq People, is covered by the historic Treaties of Peace and Friendship. These lands have long been a place of ceremony and traditional teachings, and we honor the Mi’kmaq People, past, present, and future, who have cared for this land for over 12,000 years.

This action plan seeks to meaningfully incorporate Indigenous Knowledge, culturally significant species, and community perspectives. The development of this Multi-Species Action Plan has been a collaborative effort with the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia, a partnership built over years of trust and shared understanding. Recognizing the essential role of Mi’kmaq knowledge in conservation, we have worked together through community visits, joint gatherings, and the Nuji-kelotaqitijik (Earth Keepers) program, fostering relationships that have directly shaped this plan. This spirit of collaboration will continue beyond the plan’s creation and remain central to the ongoing conservation efforts on these lands.

We would also like to acknowledge the many key partners whose expertise has been instrumental in enhancing our understanding of species at risk and their habitats. We are grateful for the contributions of the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq and Wasoqopa’q First Nation Earth Keepers, Kwilmu’kw Maw-klusuaqn (KMKNO), Ulnooweg Education Centre, Atlantic Canada Conservation Data Centre, Birds Canada, Canadian Museum of Nature, Clean Annapolis River Project, Coastal Action, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Mersey Tobeatic Research Institute, Mount Allison University, NS Department of Lands and Forestry, our neighboring Parks Canada Field Units in the Atlantic Region, and various Recovery Teams.

Lastly, we recognize and thank the people who share this land and its ecosystems. To the surrounding landowners, Kejimkujik visitors, and all those who feel a connection to these lands, your appreciation and support are vital to the continued protection of the species that call this place home.

Wela’liek, Merci, Thank You.

Executive Summary

This Multi-species Action Plan for Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site of Canada and National Historic Sites Administered by Parks Canada in Mainland Nova Scotia updates and replaces content in the Multi-species Action Plan for Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site of Canada (Parks Canada Agency, 2017), hereafter referred to as the 2017 action plan. It applies to lands and waters occurring within the boundaries of Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site (KNPNHS), Kejimkujik National Park Seaside (Kejimkujik Seaside), nine National Historic Sites and one National Historic Event in Mainland NS (NHSs of Mainland NS). The plan identifies measures to conserve or recover SARA-listed species, species of conservation concern, and culturally important species that regularly occurFootnote 3 in Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS and fulfills SARA section 47 requirements for those species that require an action plan. In the spirit of the recently signed Toqi’maliaptmu’k Arrangement (2025), the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia and Parks Canada are working towards the co-management of Kejimkujik which is reflected in the development and implementation of this plan. In Mi’kmaq, Toqi’maliaptmu’k means “we will look after it together”. Considerations related to Indigenous conservation and cultural species, landscape-scale conservation, climate-smart conservation, and ecological connectivity were central themes in the development of this action plan.

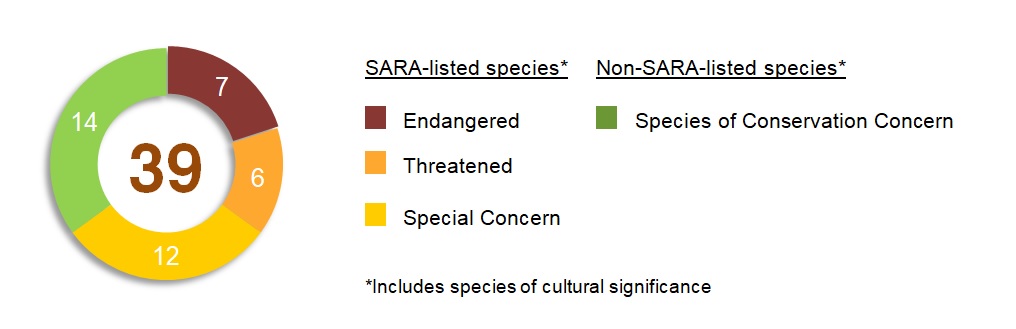

39 species that regularly occur in Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS are addressed in this action plan: 25 SARA-listed species and 14 additional species of conservation concern e.g., COSEWIC assessed but not SARA-listed, provincially listed and/or culturally significant species. Thirteen of the SARA-listed species are Extirpated, Endangered, or Threatened (and require an action plan as per SARA) and 12 are Special Concern. Six culturally significant species have been identified for inclusion by the Mi’kmaq of NS that are not currently SARA-listed. Including non-SARA-listed species of conservation concern and species of cultural importance provides a comprehensive plan for species conservation and recovery at the site.

Long description of diagram

A donut diagram showing this action plan covers 39 total species, including 7 Endangered species, 6 Threatened species, 12 Special Concern species, 14 non-SARA listed species of conservation concern including species of cultural significance to the Mi’kmaq of NS.

5 site-based population and distribution objectives are identified in this plan and represent the site’s contribution to range-wide objectives for the species as identified in SARA recovery strategies and management plans. Measuring progress towards achieving site-based objectives over time will determine the ecological impacts of implementing the action plan.

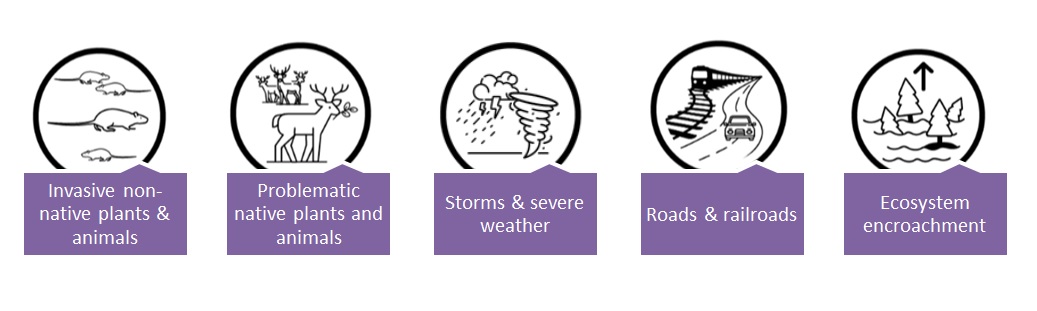

Conservation and recovery measures were developed to mitigate the main threats to the species within Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS. The presence of knowledge gaps was the most prevalent threat, identified for 52% of the measures in Appendix B. Additional threatsFootnote 4 to species addressed within committed measures in this action plan are:

Long description of diagram

Five graphic bubbles depicting the five main threats to species at risk in KNPNHS and NHSs in Mainland NS which are: invasive non-native plants and animals, problematic native plants and animals, storm & severe weather, roads & railroads, and ecosystem encroachment.

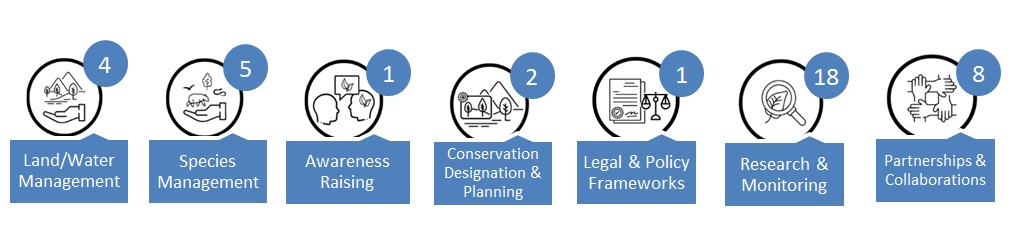

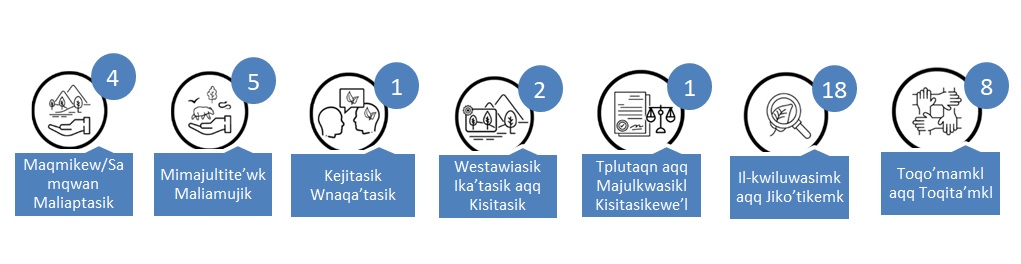

32 conservation and recovery measures are identified as commitments in this action plan. An additional 61 measures will be implemented if resources and/or partnerships become available to support the work. The number of committed measures and their action categorizationsFootnote 5 are presented below:

Long description of diagram

Seven graphic bubbles depicting seven recovery action categories in KNPNHS and NHSs in Mainland NS, which are: 4 land and water management actions, 5 species management actions, 1 awareness raising action, 2 conservation designation & planning actions, 1 legal policy & frameworks action, 18 research and monitoring activities and 8 partnership and collaboration actions.

Critical habitat identified in the 2017 action plan for Eastern Ribbonsnake remains in place to ensure continuity of legal protection. Once the regional Eastern Ribbonsnake recovery strategy is amended to include this habitat, this action plan will be amended, and section 4.1 will be removed. Additional critical habitat for Vole Ears Lichen is identified in this action plan beyond what was previously included in the 2017 action plan. Measures to protect critical habitat identified for species addressed in this plan are described.

The financial cost to implement this action plan will be borne by Parks Canada, and through partnerships if resources become available. The main impacts of implementing the measures in this plan are expected to be minimal, mainly caused by restricted access to areas of Kejimkujik Seaside during Piping Plover breeding season and a ban on the importation of firewood into KNPNHS. Benefits of this action plan include the targeted recovery of species at risk and an overall positive impact on biodiversity, contributing to federal and global sustainability goals. Benefits also include enhanced landscape-scale initiatives through increased collaboration opportunities with partners, engagement opportunities for volunteers to participate in species conservation, and application of a holistic approach across all measures, including integration of Etuaptmumk (two-eyed seeing) and other cultural priorities.

Progress toward implementation of this action plan and meeting the site-based population and distribution objectives will be assessed annually and a report summarizing the results will be published on the Species at Risk Public Registry after five years, as per section 55 of SARA.

Kisa’tikekewey Kaqiwikasik

Ula Milamuksultijik-mimajultite’wk Tel-lukwemk Kisitasik ukjit Kejikumkujik Nationaley Amalitasikewey Sa’qewey Etek ta’n Kana’ta aqq Nationale’l Sa’qewe’l Etekl Iknmuetasik ta’n Amalitasikl Kana’ta ta’n Msit-maqmikew No’pa Sko’sa wnaqitoql aqq apaji-ika’toq ewikasik ta’n na Milamuksultite’wk-mimajultite’wk Tel-lukwek Kisitasik ukjit Kejimkujik Nationaley Amalitasik aqq Nationaley Sa’qewey Etek ta’n Kana’ta (Amalitasikl Kana’ta Etl-lukwemk, 2017), tett-kaqiaq nestmalsikewtasik ta’n na elt 2017 tel-lukwek kisitasik. Ula nasiwikasik ta’n maqmikal aqq samqwann telitpiaq ta’n etl-we’tuteskasik ta’n Kejimkujik Nationaley Amalitasik aqq Nationaley Sa’qewey Etek (KNPHS), Kejimkujik Nationaley Amalitasik Apaqtukewey (Kejimkujik Apaqtukewey), pesqunatek te’sekl Nationale’l Sa’qewe’l Etekl aqq newte’ Nationaley Sa’qewey Telitpiaq ta’n Msit-maqmikew NS (NHSs ta’n Msit-maqmikew NS). Ta’n kisitasik nemitoql enkatkl ukjit westawiatmn aqq apaji-msnmn SARA-ewikasultijik mimajultite’wk, mimajultite’wk ta’n westawialujik despite’tmujik, aqq telo’ltimk nuta’jik mimajultite’wk ta’n apjiw telitpiaqFootnote 6 ta’n Kejimkujik aqq NHSs ta’n Msit-maqmikew NS aqq weju’peka’toq SARA Tepkistek 47 nuta’ql ukjit ula nekemowk mimajultite’wk ta’n nuta’tij na tel-lukwek kisitasik. Ta’n na kjijaqmik na ta’n kejikow ewi’kiksipnek Toqi’maliaptmu’k Kiskaja’tu’k (2025), ta’n Mi’kma’q na No’pa Sko’sa aqq Amalitasikl Kana’ta na elukwutijik pesu’kwatmi’tij na toqi-maliaptasik na Kejimkujik ta’n na apajapa’sik ta’n na eltasik aqq ewe’wasik ula ta’n kisitasik. Ta’n Mi’kma’q, Toqi’maliaptmu’k teluek “kinu na elt toqi-jiko’ttesnu.” Mikuaptmkl wiaqtekl na L’nueyey westawiatmk aqq telo’ltijik mimajultite’wk, maqmikewitasik-enkasik westawiasik, wksitqamukewey-seskwe’kewey westawiasik, aqq ecological toqijoqa’sikl na mekwaye’kewe’kl wisunkl ta’n na kisitasik ula ta’n tel-lukwek kisitasik.

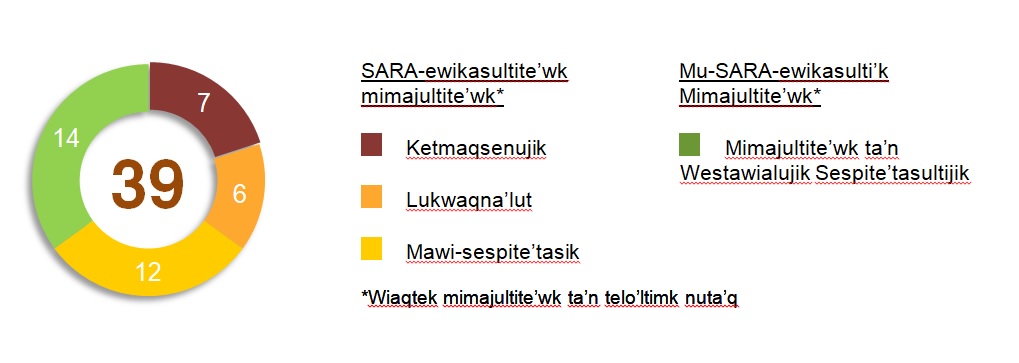

39 mimajultite’wk ta’n kaqisk telitpiaq na Kejimkujik aqq NHSs ta’n Msit-maqmikew NS na wesku’tasik ta’n ula tel-lukwek kisitasik: 25 SARA-ewikasultijik mimajultite’wk aqq 14 me’ mimajultite’wk ta’n westawialujik sespite’tmujik e.g., COSEWIC jikeyujik katu mu SARA-ewikasultijik, provincially ewikasultijik aqq/kisna telo’ltimkewe’k nuta’jik mimajultite’wk. Newtiska’q jel si’st ta’n SARA-ewikasultijik mimajultite’wk na Ketmaqseto’tkik, Ketmaqsenutkik, kisna Lukwaqna’lujik (aqq nuta’q na tel-lukwek kisitasik elt ta’n SARA) aqq 12 na Mawi-Sespite’tasik. Asukom telo’ltijik nuta’jik mimajultite’wk na ta’n nenusnik ukjit wiaqa’luksinew ta’n na Mi’kma’q ta’n NS ta’n na mu nike’ SARA-ewikasultite’wk. Wiaqtek mu-SARA-ewikasulti’k mimajultite’wk ta’n westawialujik sespite’tmujik aqq mimajultite’wk ta’n telo’ltimk nuta’q iknmuetoq na nestasik kisitasik ukjit mimajultite’wk westawialujik aqq apaji-msnujik ta’n na etek.

Long description of diagram

A donut diagram showing this action plan covers 39 total species, including 7 Endangered species, 6 Threatened species, 12 Special Concern species, 14 non-SARA listed species of conservation concern including species of cultural significance to the Mi’kmaq of NS. Text is written in Mi’kmaq.

5 etek-wiaqtek te’sek aqq iknmuetasik tel-lukwutimkl na nenasikl ta’n ula kisitasik aqq apoqnmatk ta’n etek iknmuetoq ta’n tel-knekk-teliske’k tel-lukwutimkl ukjit ta’n mimajultite’wk na nenujik ta’n SARA apaji-msnut ewi’kmkl aqq maliaptasikl kisitasikl. Enkatmk sa’se’wa’sik eliaq mesnmk etek-wiaqtek tel-lukwutimkl asoqmtaqtek ajiaq na kjijitutew ta’n Ecologicale’l we’tuwe’kl ta’n ewe’wasik ta’n tel-lukwek kisitasik.

Westawiasik aqq apaji-msnmk enkasikl na kisitasikl ukjit nisa’tun ta’n mawki’kl lukwaqna’tikekl ta’n na mimajultite’wk elt Kejimkujik aqq NHSs ta’n Mawki’k-maqmikew NS. Ta’n etek na kjijitaqne’l tepkisa’tikekl na ta’n mawi-pmiaq lukwaqna’tikek, nenasik ukjit 52% ta’n na enkasikl ta’n Ewikasik B. Anku’tekl lukwaqna’tikeklFootnote 7 ta’n mimajultite’wk aknutmujik elt melkuktmi’tij enkasikl ta’n ula tel-lukwek kisitasik na:

Long description of diagram

Five graphic bubbles depicting the five main threats to species at risk in KNPNHS and NHSs in Mainland NS which are: invasive non-native plants and animals, problematic native plants and animals, storm & severe weather, roads & railroads, and ecosystem encroachment. Text is written in Mi’kmaq.

32 westawiasik aqq apaji-msnmk enkasikl na nenasikl ta’n melkuktasikl ta’n ula tel-lukwek kisitasik. Ta’n ankuwa’sik 61 enkasikl na elt we’wasiktital ta’n tujiw apoqnmuekl aqq/kisna toqo’mamk na etekl ukjit apoqnmatmn ta’n lukwaqn. Ta’n kiljaqn na melkuktasik enkasikl aqq nekemowk tel-lukwek tepkisa’tasiklFootnote 8 na seya’tasikl lame’k:

Long description of diagram

Seven graphic bubbles depicting seven recovery action categories in KNPNHS and NHSs in Mainland NS, which are: 4 land and water management actions, 5 species management actions, 1 awareness raising action, 2 conservation designation & planning actions, 1 legal policy & frameworks action, 18 research and monitoring activities and 8 partnership and collaboration actions. Text is written in Mi’kmaq.

Nuta’ql wikultimk nenasik ta’n na 2017 tel-lukwek kisitasik ukjit Wjipnukewey Saklo’piey-mte’skm eyk me’ na’te’l ukjit kjijitun siawa’sik tplutaqn kelpitasik. Ne’wt ta’n kikjukewey Wjipnukewey Saklo’piey-mte’skm apaji-msnk ewi’kek na anqa’tasik ukjit wiaqa’tun ula wikimk, ula tel-lukwek kisitasik na ta’n naqa’tasiktitew, aqq tepkistek 4.1 na ta’n jikla’tasiktitew. Anku’tek nuta’q wikimk ukjit Nipi’je’l Wksituwaqnn Lichen na nenut ta’n ula tel-lukwek kisitasik piamu ta’n na wiaqteksipnek ta’n na 2017 tel-lukwek kisitasik. Enkasikl ukjit klpitmn nuta’q wikimk nenasik ukjit mimajultite’wk ewi’tujik ta’n ula kisitasik na ewi’tasik.

Ta’n suliewey telawtik ukjit we’wmn ula tel-lukwek kisitasik na ta’n weskwijinuiktitew ukjit Amalitasikl Kana’ta, aqq wejiaq toqo’mamkl na apoqnmuekl wejiaq etek. Ta’n msit we’tuwe’kl na ewe’wasikl ta’n enkasikl ta’n ula kisitasik na ajipjutasik ukjit na mawi-tekle’jk, msit tela’luek na mu-asite’tasiktnuk piskwa’n ta’n etekl ta’n Kejimkujik Apaqtuke’l miawiaq Piping Plover nikwenawet ika’q aqq na anqa’tasik na ta’n alkitasik ta’n puksukl ta’n KNPNHS. Welapetmkl ta’n ula tel-lukwek kisitasik wiaqtek na eltaqa’mujik apaji-msnuksinew ta’n mimajultite’wk ta’n lukwaqna’lujik aqq ta’n msit tetpqtek we’tuwe’k ta’n mimajuaqn-sa’se’wa’sik, iknmuetoq ta’n federaley aqq wksitqamukewey westawiatmkl mesnmkl. Welapetmkl ma’wt wiaqtek naji-petlewa’tasik maqmikewitasik-enkasik tel-lukwutimkl wejiaq wnaqa’sik toqilukwutimk elukwutimkl elt toqo’ma’timkik, tel-lukwen elukwutimkl ukjit nuji-apoqnmua’tite’wk ukjit tl-lukwutinew ta’n mimajultite’wk westawialujik, aqq nasiwikasik na ta’n msit pesu’kwatmk asoqmtaqtek msit enkasikl, wiaqtek sa’se’wa’sik ta’n Etuaptmumk (Etuaptmumk) aqq pilewe’l tel-lukwutimkl nuta’ql.

Sa’se’wa’sik eliaq ewe’wasik ta’n ula tel-lukwek kisitasik aqq welteskujik etek-wiaqtek te’sultijik aqq iknmuetasik tel-lukwutimkl elt na ankaptasiktital te’sipunqwek aqq na ewikasik msit-ewi’kmk ta’n ika’ql na tujiw seya’tasiktital elt ta’n Mimajultite’wk ta’n Lukwaqna’lujik Msit Nasiwikasultimk pemiaq na’n te’sipunqwekl, ke’sk na tepkistek 55 ta’n SARA.

1. Context

This Multi-species Action Plan for Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site of Canada and National Historic Sites administered by Parks Canada in Mainland Nova Scotia updates and replaces content in the 2017 action plan (Parks Canada Agency, 2017). Under section 52 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA), the competent minister may amend an action plan at any time. An amendment is being undertaken now to update species information and integrate knowledge and new information gained during implementation of the 2017 action plan. The five-year implementation report for the 2017 action plan is available on the Species at Risk Public Registry (Parks Canada Agency, 2022).

1.1 Parks Canada Multi-species Action Planning

Parks Canada takes a multi-species, site-based approach to action planning that identifies and prioritizes conservation and recovery measures for a suite of species at one or more Parks Canada sites. This approach enables Parks Canada to consider the needs of multiple species and identify and prioritize measures that can be implemented at the site(s) to provide the greatest contributions to species conservation and recovery.

Parks Canada multi-species action plans focus on lands and waters under Parks Canada’s administration; however, Indigenous communities, neighbouring jurisdictions, partners, interest groups, and species and subject-matter experts are engaged throughout development and implementation of the plans. This collaborative approach facilitates cooperation on species conservation and recovery at a landscape scale.

The action planning process considers a suite of species that occur regularly at the site(s), including species at risk (SAR) listed in Schedule 1 of SARA, species assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) and under consideration for addition to Schedule 1 of SARA, provincially listed species, and other species of interest, including those of cultural importance. Taking this holistic approach enables Parks Canada to develop a comprehensive plan for species conservation and recovery at the site(s).

In many cases, federal and provincial recovery strategies and plans, management plans, and action plans have been prepared for the species included in this action plan. Along with COSEWIC status assessments, those documents provide guidance for the recovery of individual species, including the identification of threats, recovery objectives, strategic direction to achieve objectives, and identification of critical habitat. This action plan is consistent with those recovery documents and should be viewed as part of this body of linked strategies and plans.

Parks Canada’s approach to multi-species action planning aligns with the Pan-Canadian Approach to Transforming Species at Risk Conservation in CanadaFootnote 9 (Canadian Wildlife Service, 2018) and considers priorities of landscape-scale conservation, ecological connectivity, climate-smart conservation, Indigenous conservation, and cultural species. In addition, Parks Canada is increasingly using the adaptive management framework Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation (i.e., Conservation Standards)Footnote 10 to support and inform the action planning process.

Implementation of the conservation and recovery measures identified in these action plans is often integrated into the existing framework of Parks Canada conservation programs. Ecological integrity is a cornerstone of Parks Canada’s mandate to protect and present significant examples of Canada’s natural heritage. It is the first priority in the management of Canada’s National Parks. In addition to the protections provided under SARA, species at risk, their residences, and their habitat in Parks Canada administered places are often protected under additional federal acts and regulations, including but not limited to the Migratory Birds Convention Act and regulations, Fisheries Act, Canada National Parks Act, and the Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act.

1.2 Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site and National Historic Sites Administered by Parks Canada in Mainland NS

This amended action plan encompasses Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site (hereafter KNPNHS), Kejimkujik National Park of Canada Seaside (hereafter Kejimkujik Seaside), and ten National Historic Sites across Mainland Nova Scotia (hereafter NHSs of Mainland NS). KNPNHS and Kejimkujik Seaside hereafter will be collectively referred to as Kejimkujik. All sites are in the unceded traditional Mi’kmaw territory of Mi’kma’ki. The Nova Scotia Peninsula, part of the province’s mainland, is characterized by numerous bays and estuaries with no location being more than 67 km from the ocean. According to Mi’kmaq oral traditions, Mi’kma’ki is divided into seven districts, one of which is Kespukwitk—meaning "lands end" or "end of flow". Kespukwitk encompasses KNPNHS, Kejimkujik Seaside and four associated NHSs, and is renowned for its exceptional biodiversity, the presence of numerous species at risk, and its cultural significance. Kespukwitk is home to a variety of ecosystems and habitats, ranging from rugged coastlines and protected bays to coastal islands, lakes, rivers, wetlands, fertile valleys, and expanses of Wabanaki (Acadian) Forest, including some of the largest remaining intact forests in Nova Scotia.

KNPNHS was formally established as a national park in 1974 with Kejimkujik Seaside acquired from the province in 1985 and designated as part of the park in 1988. These two areas protect 403 km2. Kejimkujik is a place where, for generations, people have connected to nature and culture in a landscape of forests, wetlands, lakes, and the Atlantic coast. KNPNHS was established to protect representative examples of the Atlantic Coastal Uplands Region. Its forests include mixed coniferous and deciduous vegetation comprised of tree species including American Beech, Yellow Birch, Eastern Hemlock, Sugar Maple, White Pine, Red Oak, and Red Spruce. This is often described as the Wabanaki-Acadian Forest type, with a high level of understory plant and animal diversity. The aquatic ecosystems reflect the influence of shallow, acidic, warm water lakes, still waters, and meandering streams featuring significant seasonal water level changes. Kejimkujik Seaside was established to provide protection for the unique coastal attributes of this region. Kejimkujik and the broader cultural landscape, including the Mersey River Corridor, have a profound ecological and cultural significance to the Mi’kmaq. Kejimkujik also has significance as a place of recreation, respite, and connection for both new and returning visitors, and to local communities with deep ancestral and historical connections.

KNPNHS was designated a national historic site in 1995 because it is a significant Mi’kmaw cultural landscape that attests to Mi’kmaw occupancy and use of the area from time immemorial. The Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia worked closely with Parks Canada to seek this designation. Within the landscape, many important cultural resources can be found, including pre-contact habitation sites, post-contact reserve sites, petroglyphs, canoe routes and portages, fishing weirs and sacred sites. The wilderness character of KNPNHS is an integral part of this cultural landscape. At Kejimkujik Seaside, Mi’kmaq used the coast for hunting and gathering while camping in the surrounding harbours. At the time of European expansion into North America, the Mi’kmaq occupied a vast territory in what is now Atlantic Canada.

In 2001, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) designated the five counties of southwest Nova Scotia (Annapolis, Digby, Yarmouth, Shelburne, and Queens) as a biosphere reserve in recognition of the area’s rich biodiversity and cultural history. KNPNHS, the Tobeatic Wilderness Area, and a portion of the Shelburne River (a Canadian Heritage River) function as the core protected area for the Southwest Nova Biosphere Reserve. This reserve is the second largest in Canada and first to be designated in Atlantic Canada. It focuses on regional cooperation and sustainable development.

The larger Kespukwitk landscape also closely corresponds to the Kespukwitk / Southwest Nova Scotia Priority Place, which is one of eleven Priority Places established in Canada by the Federal, Provincial and Territorial governments. Priority Places were identified under the Pan-Canadian Approach to Transforming Species at Risk Conservation in Canada (Canadian Wildlife Service, 2018) to highlight regions of high biodiversity where partnerships and conservation efforts could be maximized for species at risk and ecosystems.

The NHSs of Mainland Nova Scotia are divided into two regions: (1) Southwest Nova Scotia and (2) the Halifax Defense Complex. The Southwest Nova Scotia region includes Port-Royal, Fort Anne, Melanson Settlement, and Fort Edward in the Annapolis Valley, which are located within Kespukwitk, a region known for its fertile farmland, agriculture, fisheries, and tourism. The Halifax Defense Complex, recognized in 1965 for its historical importance as a major British naval station, comprises of Georges Island, Fort McNab, York Redoubt, Prince of Wales Tower, and the Halifax Citadel. These former military sites were transferred from the Department of National Defense to Parks Canada between 1936 and 1964. These sites protect heritage resources to maintain commemorative integrity, ensure preservation of cultural resources, and communicate the site’s historical importance and heritage. Natural features often central to the site’s history and landscape are also valued, underscoring Parks Canada’s role as an environmental steward. Beyond preservation, these sites provide visitors with the chance to connect with and experience the rich culture and history of Nova Scotia from diverse perspectives.

1.3 Scope of the action plan

In addition to Kejimkujik, the geographic scope of this amended action plan includes the NHSs of Mainland NS which were not included in the previous action plan and are within and administered by the Mainland Nova Scotia Field Unit of Parks Canada.

1.3.1 Geographic scope

The geographic scope of this action plan includes all federally administered lands and waters managed by Kejimkujik and all lands and waters within the boundaries of NHSs of Mainland NS that are administered by Parks Canada as federal properties under the authority of the Federal Real Property and Federal Immovables Act. The NHSs of Mainland NS include Halifax Citadel NHS, Georges Island NHS, York Redoubt NHS, Fort McNab NHS, the Prince of Wales Tower NHS, Fort Edward NHS, Fort Anne NHS, Melanson Settlement NHS, and Port-Royal NHS and Isgonish-French River Portage NHE (National Historic Event) (Figure 1). This action plan has been written specifically for Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS to fulfill Parks Canada’s legal responsibilities, and to respond to specific threats, legislation, and management priorities at those sites, which may differ in areas outside the sites.

This plan has been developed collaboratively and may be implemented beyond the lands administered by Parks Canada by working with various partners in the broader landscape to maximize conservation benefits to species conservation and recovery. Kejimkujik and the associated NHSs of Mainland NS represent only a small portion of Kespukwitk (Southwest Nova Scotia) and Mik’ma’ki and the species at risk within its boundaries are not confined to this area, nor are the threats they face. As such, the plan considers the larger Kespukwitk landscape. Most of the conservation and recovery measures taking place in the greater Kespukwitk landscape (outside of Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS) will be led by partners. In the spirit of collaboration, Parks Canada will provide support when resources allow.

Text description

Figure 1 is a map showing the location of KNPNHS, Kejimkujik Seaside (both shown in dark green shaded polygons) and nine national historic sites including (each indicated by a red triangle) Halifax Citadel NHS, Georges Island NHS, York Redoubt NHS, Fort McNab NHS, the Prince of Wales Tower NHS, Fort Edward NHS, Fort Anne NHS, Melanson Settlement NHS, and Port-Royal NHS and Isgonish-French River Portage NHE (National Historic Event). The map also shows the surrounding geographic area of the Kespukwitk district (outlined in purple), including the Tobeatic Wilderness Area (shown as a light green shaded polygon).

1.3.2 Species scope

This action plan addresses 25 SARA-listed species and 14 species of conservation concern that regularly occur in Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS (Table 1). This includes 13 SARA-listed Extirpated, Endangered, or Threatened species (for which an action plan is required under s.47 of SARA) and 12 SARA-listed Special Concern species. Six culturally significant species have been identified for inclusion by the Mi’kmaq of NS that are not currently listed under SARA. Additional marine species which occur outside of lands administered by Parks Canada are addressed by one recovery measure within this plan (measure 16), though not explicitly listed in the species scope. The species addressed in this plan were chosen based on the following criteria: 1) the level of influence Parks Canada and partners could have on recovery and helping to achieve population and distribution objectives; 2) the ability of the species to represent the needs of other species at risk; 3) the need for regional perspectives and desire to test existing approaches to species conservation to inform effectiveness; 4) the identification for inclusion of culturally significant species by the Mi’kmaq of NS. Over the course of implementation of this action plan, some species’ COSEWIC assessment or SARA status may change.

| Species Common Name | Mi’kmaq NameFootnote 11 | Scientific Name | COSEWIC status | SARA Schedule 1 status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piping Plover (melodus subspecies) | Aldoqsanèj (plover) | Charadrius melodus | Endangered | Endangered |

| Monarch Butterfly | Mimikej (butterfly) | Danaus plexippus | Endangered | Endangered |

| Vole Ears Lichen | Erioderma mollissimum | Endangered | Endangered | |

| Blanding’s Turtle (Nova Scotia population) | Amalegunoktcētc | Emydoidea blandingii | Endangered | Endangered |

| Little Brown Myotis | Tupkwanamuksit na’jipuktaqne’ji’j | Myotis lucifugus | Endangered | Endangered |

| Northern Myotis | Oqwatnukewey na’jipuktaqnej |

Myotis septentrionalis | Endangered | Endangered |

| Tri-coloured Bat | Na’jipuktaqnej (bat) | Perimyotis subflavus | Endangered | Endangered |

| Black-foam Lichen | Anzia colpodes | Threatened | Threatened | |

| Chimney Swift | Gaqtugòbnchìj | Chaetura pelagica | Threatened | Threatened |

| Wrinkled Shingle Lichen | Pannaria lurida | Threatened | Threatened | |

| Eastern Ribbonsnake (Atlantic population) | Elapaqtekjijk | Thamnophis sauritus | Threatened | Threatened |

| Canada Warbler | Watapji’jit ketapekiejit | Cardellina canadensis | Special Concern | Threatened |

| Barn Swallow | Pukwales (swallow) | Hirundo rustica | Special Concern | Threatened |

| Yellow-banded Bumble Bee | Amu (bee) | Bombus terrucola | Special Concern | Special Concern |

| Common Nighthawk | Pi’jkwej (nighthawk) | Chordeiles minor | Special Concern | Special Concern |

| Snapping Turtle | Mikjikj (turtle) | Chelydra serpentina | Special Concern | Special Concern |

| Eastern Painted Turtle | Mikjikj (turtle) | Chrysemys picta picta | Special Concern | Special Concern |

| Evening Grosbeak | Kniskwatkiyej (grosbeak) | Coccothraustes vespertinus | Special Concern | Special Concern |

| Olive-sided Flycatcher | Sisip (bird) | Contopus cooperi | Special Concern | Special Concern |

| Eastern Wood-pewee | Wjitpenu’key Sisip | Contopus virens | Special Concern | Special Concern |

| Blue Felt Lichen | Degelia plumbea | Special Concern | Special Concern | |

| Rusty Blackbird | Pukĩtli’skiej (blackbird) | Euphagus carolinus | Special Concern | Special Concern |

| Water Pennywort | Nipi (plant) | Hydrocotyle umbellata | Special Concern | Special Concern |

| Frosted Glass Whiskers (Atlantic Population) | Sclerophora peronella | Special Concern | Special Concern | |

| Long’s Bulrush | Nipi (plant) | Scirpus longii | Special Concern | Special Concern |

| Eastern Red Bat | Na’jipuktaqnej (bat) | Lasiurus borealis | Endangered | Under consideration for addition |

| Hoary Bat | Na’jipuktaqnej (bat) | Lasiurus cinereus | Endangered | Under consideration for addition |

| Silver-haired Bat | Na’jipuktaqnej (bat) | Lasionycteris noctivagans | Endangered | Under consideration for addition |

| Atlantic Salmon (Nova Scotia Southern Upland population)*+ | Plamu (salmon) | Salmo salar | Endangered | Under consideration for addition |

| American Eel* | Katew (eel) | Anguilla rostrata | Threatened | Under consideration for addition |

| Black Ash* | Wisqoq | Fraxinus nigra | Threatened | Under consideration for addition |

| Scaly Fringe Lichen** | Heterodermia squamulosa | Threatened | Under consideration for addition | |

| White-rimmed Shingle Lichen | Fuscopannaria leucosticta | Threatened | Under consideration for addition | |

| Mainland Moose* | Tia’m (moose) | Alces americana | Not assessed | Not listed |

| White Ash* | Aqamoq | Fraxinus americana | Not assessed | Not listed |

| American Marten* | Apistane’wj (marten) | Martes americana | Not assessed | Not listed |

| Perforated Ruffle Lichen++ | Parmotrema perforatum | Not assessed | Not listed | |

| Brook Trout | Atoqwa’su (trout) | Salvelinus fontinalis | Not assessed | Not listed |

| Eastern Hemlock | Ksu’sk | Tsuga canadensis | Not assessed | Not listed |

*Indicates culturally important species (that are not listed under SARA) to the Mi’kmaq of NS

+ In KNPNHS historically

** Occurs directly outside KNPNHS and advised by lichenologists to be likely present in KNPNHS

++ Only known to occur in 2 places in Canada, including KNPNHS

2. Site-based population and distribution objectives

The potential for Parks Canada to undertake direct management action at the site that will measurably contribute to the recovery of each species was assessed. Site-specific population and distribution objectives were developed for five species (Appendix A). These objectives identify the contribution that conservation and recovery measures implemented by the site or in collaboration with partners can make towards achieving the range-wide objectives identified in SARA recovery strategies and management plans. An ecosystem-level focus on collective actions with partners and other national parks and sites over a species range can yield conservation impacts that go beyond the individual site. The development of recovery measures in this action plan incorporates a landscape-scale approach, ensures recovery measures align with regional recovery documents, and focuses on collaborative actions with partners to maximize conservation gains.

Monitoring progress towards achieving the site-based objectives over time will help determine whether implementation of the conservation and recovery measures (identified in Appendix B and when possible, in Appendix C) is having the desired influence on species recovery.

For several species, Parks Canada’s primary contribution to conservation is ensuring that protection measures are maintained to protect species and their habitats. In these cases, recovery cannot be measurably influenced by site-level management actions, and therefore, setting site-specific population and distribution objectives are not appropriate. This may be due to one or more of the following circumstances within the site: (1) there are no or few known threats; (2) there are no feasible management actions to address threats; or (3) only a small portion of the species range is within the site and therefore the impact of management actions cannot be measured. In such cases, conservation efforts may be limited to protection measures in place under federal legislation, including the Canada National Parks Act, the Impact Assessment Act, the Fisheries Act, Migratory Birds Convention Act, and SARA. Additional efforts may include indirect threat mitigations such as education and outreach, habitat maintenance, and addressing knowledge gaps through inventory, research, and monitoring.

3. Conservation and recovery measures

Conservation and recovery measures aimed at addressing threats to the species at the site and making progress towards achieving site-based population and distribution objectives were identified and prioritized. The prioritization process primarily considered ecological effectiveness, but also considered opportunities for landscape-scale conservation, ecological connectivity, climate-smart conservation, Indigenous conservation and cultural species, strengthened partnerships, and opportunities for visitor experience and increased awareness through education and outreach. Prioritization also considered budgetary opportunities and feasibility. Wherever possible, Parks Canada is taking an ecosystem approach, prioritizing measures that benefit multiple species to maximize the effectiveness and efficiency of species protection and recovery.

In total, 32 conservation and recovery measures are identified for implementation in Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS (Appendix B). An additional 61 measures will be encouraged through partnerships or when additional resources become available (Appendix C). Each measure is associated with one or more identified threats. In addition to knowledge gaps which is the most prevalent threat identified (52%), the next five threats addressed by this action plan from the Conservation Measures Partnership Direct Threats Classification (version 2.0) are: invasive non-native plants & animals; problematic native plants and animals; storm & severe weather; roads and railroads; and ecosystem encroachment. Each measure is also associated with an objective and the anticipated timeline for achieving the outcome. Recovery measure objectives are designed to be quantifiable and achievable over the 10-year implementation period of this plan.

3.1 Conservation and recovery measure approaches

Indigenous Conservation & Cultural Species:

Kejimkujik worked in collaboration with the Mi’kmaq of NS in the development of this action plan to support Indigenous conservation objectives: protecting biodiversity, preserving Mi’kmaq culture and language, incorporating the principles of EtuaptmumkFootnote 12 (two-eyed seeing) and NetukulimkFootnote 13 (a holistic-ecosystem approach), and strengthening collaboration opportunities. A foundation of trust and collaboration was built over years with a priority on establishing meaningful relationships within community through joint gatherings, community visits, shared learning, and through relationships and partnerships built within the Earth Keepers program. The importance of time and space to build meaningful relationships and a structure for collaborative planning and implementation cannot be underestimated. This strong partnership has led to the development of measures in this plan such as a community Katew (American Eel) monitoring program in dammed and undammed river systems and mitigating threats to Wisqoq (Black Ash). This collaboration will continue beyond the development of this plan with the intent to implement a Etuaptmumk approach to species at risk and cultural species stewardship.

A gathering with the Mi’kmaq of NS was held during the development of this plan, focusing on the conservation of species of cultural importance. The gathering featured dialogue and collaboration around a fire, where participants celebrated ongoing conservation efforts, identified knowledge gaps, and discussed strengthening partnerships for future conservation initiatives. It was acknowledged that all species hold cultural significance, and that continued dialogue is essential to inform future projects and partnerships. Cultural measures were co-developed during this workshop with the aim of strengthening ongoing relationships and acknowledging knowledge gaps by supporting and fostering youth and elder gatherings, as well as applying a two-eyed and holistic approach. Figure 2 showcases the graphic created to capture the key discussions during the gathering. Flexibility and collaboration with Earth Keepers will be prioritized throughout the implementation of this plan.

The workshop highlighted the importance of involving youth in both traditional practices and conservation efforts as a critical strategy for addressing knowledge gaps. Kejimkujik’s commitment to supporting such relationship-building initiatives reinforces the foundation for continued collaboration, ensuring that future generations of Mi’kmaq can continue their traditions while protecting the natural world. This workshop marks the beginning of a long-term effort to fill knowledge gaps related to species at risk and those of cultural importance. Moving forward, Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS will continue to weave in the principles of Etuaptmumk and Netukulimk into the implementation of this work. This work will happen in the context of the Toqi’maliaptmu’k Arrangement (2025), which will strengthen the relationship between the Mi’kmaq of NS and Parks Canada to steward and protect these lands for present and future generations.

Text description

Figure 2 is an infographic titled “Species of Cultural Importance – Wikevikus, September 2024.” Highlights the importance of cultural species, invasive species, traditional knowledge, and collaboration. Key themes include: all species need attention; partnerships, monitoring, and ceremony; invasive species threats; elders and youth sharing knowledge; conservation mindset in youth; rematriation of artifacts; treaty rights linked with sustainability. Emphasizes multidirectional knowledge sharing, narrowing gaps, reducing silos, and carrying cultural memory forward.

Landscape-scale Conservation:

Kejimkujik has a long history of collaborating with partners within and beyond its boundaries on species at risk recovery. The development of recovery measures in this action plan incorporates a landscape-scale approach with partners including KMKNO, Earth Keepers, Friends of Keji Cooperating Association, the Mersey Tobeatic Research Institute, the Clean Annapolis River Project, Birds Canada, ECCC, DFO, and the Provincial Government of NS. Collaborating with partners encourages the implementation of strategies at a provincial scale and enhances the outcomes for species at risk recovery in Kespukwitk.

There is a clear link to landscape-scale partnership throughout this action plan both in its planning and implementation. Recovery measures were developed collaboratively with partners through three workshops focused on the Eastern Ribbonsnake, SAR turtles (Blanding’s Turtle, Snapping Turtle, Eastern Painted Turtle), and SAR lichens (Vole Ears Lichen, Black-foam Lichen, Wrinkled Shingle Lichen, Blue Felt Lichen, Frosted Glass Whiskers, White-rimmed Shingle Lichen, and Scaly Fringe Lichen). Kejimkujik and partners have the potential to significantly influence the recovery of SAR reptiles in the area due to their range and the scope and scale of the threats to their populations. Consequently, these species have the greatest number of measures dedicated to their recovery. A cultural gathering was held to identify collaborative priorities with the Mi’kmaq of NS, recognizing the cultural importance of all species.

The development of recovery measures considered opportunities for collaboration with regional conservation initiatives. Since much of the geographic scope of this action plan falls within the Kespukwitk/Southwest Nova Scotia Priority Place, measures were deliberately aligned with the priorities of the Kespukwitk Conservation Collaborative through consistent engagement during the development of this plan. Regional partners also assessed measures relevant to their work (e.g., DFO reviewed Plamu (Atlantic Salmon) and Katew (American Eel) projects) and identified opportunities for involvement and synergies. Such partnerships will continue throughout the implementation of this plan, with Kejimkujik continuing to work collaboratively on regional priorities at a landscape scale.

Climate-smart Conservation:

This plan was developed using a climate change lens to reflect current and future climate-related threats to species at risk conservation. The climate-smart conservation approach focuses on intentional and deliberate consideration of forward-looking goals and strategies focused on key climate impacts and vulnerabilities (Stein et al., 2014). Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS are vulnerable to climate change impacts such as intensified weather extremes (drought, flooding, heat waves), an increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events, and invasive species spreadFootnote 14. This has been observed in recent years during increased post-tropical storms and significant rain events, where Kejimkujik experienced forest blow down, coastal erosion, flooding, and damage. Coastal properties may experience an accelerating rate of coastal erosion, sea-level rise, and storm surgesFootnote 15. Relative sea level is projected to increase by about 50 cm by 2070 at Kejimkujik Seaside (Parks Canada Agency, 2024b).

This action plan seeks to address the primary climate change threats in Kejimkujik, focusing on species most vulnerable to its effects. These climate-smart measures were informed by species at risk recovery documents, climate models for Kejimkujik (Parker & Smith, 2019; Parks Canada Agency, 2024a; Parks Canada Agency, 2024b), and a Climate Adaptation Workshop held in 2019 that focused on the current and projected impacts caused by climate change on Kejimkujik. The Resist-Accept-Direct (RAD) framework was used in this process to identify a range of potential actions that either resist change, direct change (climate-focused interventions) or accept change (Schuurman et al., 2020). Recognizing that climate change impacts are inevitable and already taking place, Kejimkujik will focus efforts on increased monitoring plans to better understand these impacts and new pressures on species, and to inform long-term adaptation approaches and potential threat mitigation. This includes monitoring turtle nest temperatures to determine if sex ratios are being impacted or chemically treating hemlock trees to reduce effects of the invasive Hemlock Woolly Adelgid.

Ecological Connectivity:

Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS are nestled within the greater Kespukwitk ecosystem and the broader provincial landscape. Ecological connectivity requirements are a key consideration for SAR planning and recovery. The actions within this plan consider outcomes beyond park and historic site boundaries to connect habitats and reduce threats as species travel across the landscape. Understanding and conserving ecological connectivity requires collaboration, partnership, and recognition that recovery actions can have greater benefits when they are carried out at an ecosystem level.

Species in this plan were assessed to determine which would be most impacted by changes in levels of connectivity (i.e., based on species/habitat characteristics and threats identified in recovery documents and COSEWIC status assessments). Mainland Moose, American Eel, and American Marten were projected to benefit the most from regional connectivity initiatives. SAR reptiles were found to benefit from increased connectivity within the park/site. Monarch Butterfly and SAR lichens were found to benefit from passive connectivity approaches where protected areas act as intact landscape patches to connect habitat on the greater landscape. Measures to assess, conserve, and/or restore connectivity range from the placement of reptile ecopassages, the assessment of freshwater connectivity related to barriers on the Mersey River for American Eel, the identification of key landscape corridors to increase functional connectivity and understanding the ecological context parks and sites play in lichen conservation. It is recognized that improving the connectivity of freshwater species will need to be balanced with potential costs (e.g., movement of invasive species).

3.2 Classification of measures

Measures identified in this plan are categorized based on Conservation Measures Partnership (CMP) Conservation Actions ClassificationsFootnote 16. The following action classifications are addressed in this plan:

Land / Water Management:

KNPNHS is renowned for its majestic old growth forests and an extensive system of lakes and rivers for paddling and fishing. Measures in this plan have been developed to address impacts from invasive species within these ecosystems, including the targeted removal of Chain Pickerel from key refuge habitats for Brook Trout and the continued use of chemical and biological controls to manage Hemlock Wooly Adelgid (HWA) in priority old growth stands. There is also an overall focus on updating and improving best management practices for species at risk in Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS to ensure that conservation and recovery efforts for these species and ecosystems are applied regionally, support the most up-to-date practices that reduce or mitigate threats and integrate Indigenous Knowledge. Additionally, recovery measures emphasize the protection of important nesting habitats and species through actions such as seasonal beach closures and road mitigations that safeguard SAR reptiles and the Piping Plover.

Species Management:

Direct management options were considered an important inclusion in this plan for species of cultural and ecological significance and those whose recovery extends beyond Kejimkujik’s boundaries. For Blanding’s Turtle this includes nest protection measures, food/waste management, and eco-passage construction which targets the threat of road mortality that not only benefits Blanding’s turtles, but other SAR reptiles and animals as well. Nest relocation measures for Blanding’s Turtle and Piping Plover address the anticipated climate change effects of increased precipitation and storm frequency, and artificial habitat creation aims to improve nesting habitats for SAR turtles and Barn Swallows.

Seed collection for Black Ash, Eastern Hemlock, and other culturally significant species will allow for the conservation of genetic diversity while also contributing to research, ecological restoration, assisted migration, and overall regional adaptation for these species in the face of climate change and invasive species impacts.

Awareness Raising:

Providing opportunities for the public to learn about and experience national parks is a central component of Parks Canada’s mandate. Therefore, in addition to the implementation of measures that directly contribute to species conservation and recovery, public education/outreach activities have been developed as part of the action planning process. These will facilitate engagement through a range of approaches and participation levels including citizen science programs, volunteer opportunities, communication strategies, and educational materials.

Kejimkujik will continue to maintain its volunteer program, providing visitors with a variety of opportunities to learn about and be involved with species at risk conservation. Additional citizen science contributions will be encouraged through submissions of wildlife sightings through online programs such as iNaturalist, social media, and staff at Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS. Development of a species at risk communication strategy and additional signage will facilitate widespread education outside of active volunteer opportunities.

Conservation Designation & Planning:

Conservation planning for restoration and recovery activities is an essential step in species-specific or multi-species recovery that helps direct future recovery efforts. Situation analyses and results chains will be updated for the Blanding’s Turtle, Eastern Ribbonsnake, Snapping Turtle, Wisqoq (Black Ash), Eastern Hemlock, and Piping Plover. Parks Canada will work with partners to improve protected land connectivity through targeted and collaborative land acquisition, benefiting numerous species in this plan.

Legal & Policy Frameworks:

Legislation and policy are valuable tools for species protection and recovery. This plan includes continued implementation of a firewood importation ban to prevent the introduction and spread of invasive forest pests to protect KNPNHS’s forests.

Research & Monitoring:

Knowledge gaps hinder the development and implementation of effective species protection, conservation and recovery efforts. Information obtained through research, surveys, and monitoring will provide a better site-level and regional understanding of species ecology, habitat, distribution, status, and population trends, allowing for better protection and timely implementation of active management and threat mitigation. Addressing these gaps also involves integrating Mi’kmaq perspectives. Measures were developed to improve understanding of Mi’kmaq priorities by weaving Etuaptmumk (two-eyed seeing) and Netukulimk (a holistic-ecosystem approach) and embedding cultural practices and language into species recovery efforts. These measures aim to build a more comprehensive and inclusive foundation for conservation work within the context of co-management with the Mi’kmaq of NS.

Part of Parks Canada’s responsibilities is to monitor ecosystem health and ecological integrity. Long-term ecological monitoring in Kejimkujik contributes directly towards species at risk through monitoring of Piping Plover, lichens, and Blanding’s Turtle, as well as indirectly through monitoring of habitats used by species at risk. Monitoring programs outlined within this plan also include tracking the health and distribution of species such as Eastern Ribbonsnake and SAR bats using techniques such as telemetry, acoustics, habitat mapping, and field surveys. Additionally, targeted monitoring will evaluate the impacts of invasive species (e.g., HWA and Chain Pickerel) and the effectiveness of management actions taken by Kejimkujik to protect Eastern Hemlock, Brook Trout, and SAR reptiles.

Research efforts focus on population studies and modeling, including collaborations with partners and academia to better understand trends and viability for species like Blanding’s Turtle. Evaluating the effectiveness of the past headstart program and the threat of nest predation will provide insight into the direction and level of protection efforts that should be prioritized in KNPNHS. Testing the application of advanced tools such as Environmental DNA (eDNA) and stable isotope analysis will increase understanding of the impacts that Chain Pickerel have on SAR reptiles. Threat assessments address climate change impacts, invasive species, and non-target effects of pesticide use in hemlock stands on sensitive species (e.g., pollinators). Habitat mapping initiatives employ technologies like drones, telemetry, and predictive modeling to refine critical habitat for SAR reptiles, SAR lichens, and Piping Plovers. Connectivity and ecosystem changes are also studied, with assessments of dam impacts on aquatic systems and the identification of landscape corridors to support species movement in Southwest Nova Scotia.

Partnerships/collaborationsFootnote 17:

Many conservation and recovery measures outlined in this plan were developed and will be implemented in collaboration with regional partners. Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS will continue working together with Mi’kmaq partners, prioritizing trust and relationship-building to foster a meaningful exchange and blending of perspectives, ideas, and knowledge from the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia. Opportunities for cultural learning and connection through knowledge and story-sharing are prioritized as an important component of the partnership along with conservation and recovery actions. Considerations for cultural species have been woven into the measures and actions throughout this plan.

Measures focused on SAR reptiles heavily rely on long standing collaboration with Friends of Keji Cooperating Association and Mersey Tobeatic Research Institute. Blanding’s Turtle nest protection measures would not be possible without the efforts of the experienced Friends of Keji Cooperating Association volunteers. Collaborative efforts with Mersey Tobeatic Research Institute, such as equivalent nest protection for adjacent Blanding’s Turtle populations (McNeil et al., 2024) and joint research efforts on other SAR reptiles including the Eastern Ribbonsnake, and SAR Bats extend conservation impacts beyond KNPNHS, creating a regional-scale approach to species recovery.

Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS will work to maintain these and other existing partnerships, as well as cultivate new ones related to conservation concerns with the species in this plan. Local communities, visitors, and volunteers will continue to be engaged through direct involvement in species recovery, education, awareness raising, and citizen science to help support the recovery of species at risk through this plan.

4. Critical habitat

Critical habitat is “the habitat that is necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed wildlife species and that is identified as the species’ critical habitat in the recovery strategy or in an action plan for the species” (SARA s.2(1)). Where the recovery strategy for a species’ states that the identification of critical habitat is not complete, a schedule of studies is included towards gathering additional information to complete the identification. Additional critical habitat can be identified in an amended recovery strategy or in a new or amended action plan for the species.

Critical habitat is identified in Kejimkujik within the recovery strategies for Piping Plover (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022a), Blanding’s Turtle (Parks Canada Agency, 2012), Black-foam Lichen (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2023), Bank SwallowFootnote 18 (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2022b) and Eastern Ribbonsnake (Parks Canada Agency, 2012). Provincial core habitat was identified in KNPNHS within the recovery plan for the American Marten (NS DNRR, 2023). For species where additional critical habitat may be identified in the future, this will be done, as appropriate through a future amendment to the species’ recovery strategy. The schedule of studies in each recovery strategy can be referred to for more information.

Critical habitat identification for Eastern Ribbonsnake and Vole Ears Lichen is outlined in section 4.1 and 4.2.

4.1 Identification of critical habitat for Eastern Ribbonsnake (Atlantic population)

4.1.1 Geographic location

In addition to the critical habitat in Kejimkujik identified in the Eastern Ribbonsnake Recovery Strategy (Parks Canada Agency, 2012), two additional areas of critical habitat were identified in the 2017 Kejimkujik action plan (Parks Canada Agency, 2017) near Grafton Lake. The protection of these areas remains in place to ensure continuity of legal protection until they are included in the amended recovery strategy for the species (Figure 3). These areas are overwintering sites, which are critical for Eastern Ribbonsnake survival (Parks Canada Agency, 2012b). The two forested overwintering sites at Grafton Lake in Kejimkujik are the first confirmed in Nova Scotia and were discovered by observing snakes in early spring and late fall. Both sites are located in mixedwood forests, approximately 150 m from the nearest wetland, in sloped and well-drained areas with numerous small underground holes. It has been observed that while snakes return to the same general site each year, the concentration spots vary, suggesting that the snakes may be using different underground holes each winter.

Critical habitat at the terrestrial overwintering site for the Eastern Ribbonsnake was identified using a similar process to the identification of wetland-based critical habitat in the species recovery strategy (Section 6.2) (Parks Canada Agency, 2012b). The following process was applied to identify the extent of the critical habitat:

- Sites were included that were confirmed as an overwintering area for two or more winters based on late fall and early spring sightings. A minimum convex polygon (MCP) was drawn around all observation points at the site.

- Critical habitat includes the area within the MCP, as well as a 100 m zone around the boundaries of the MCP to capture travel to and from the overwintering site.

This process was specific to the two overwintering sites at Grafton Lake. As more overwintering sites are identified, the process will be reviewed to determine if a standard protocol can be developed that applies to all overwintering critical habitat for Eastern Ribbonsnake.

Text description

Figure 3 is a map showing Eastern Ribbonsnake (Thamnophis sauritus) critical habitat within Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site of Canada. Yellow shaded polygons mark critical habitat, which was identified in the 2012 Recovery Strategy; green shaded polygons show the additional critical habitat identified in the action plan; and lakes represented in a darker blue colour indicate lakes identified in the Eastern Ribbonsnake recovery strategy with confirmed sightings of snakes from 2002-2012 (referred to as ‘Ribbonsnake Locations’ in the recovery strategy). The map highlights habitat distribution mainly around lakes and waterways in the park. An inset map shows the park’s location in southwestern Nova Scotia.

4.1.2 Biophysical attributes

The biophysical attributes of suitable Eastern Ribbonsnake habitat, including basking, cover, feeding/shedding, gestation, birthing and mating habitat, are detailed in section 1.81 of the recovery strategy (Parks Canada Agency, 2012b). Critical habitat for the Eastern Ribbonsnake occurs where the critical habitat criteria and methodology described in section 6.2 of the recovery strategy are met (Parks Canada Agency, 2012b). Additional criteria for the identification of overwintering site critical habitat is detailed above, as it relates to known concentration areas, and allowing for travel to and from the overwintering site.

4.1.3 Examples of activities likely to result in destruction of critical habitat

Examples of activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat are described in section 6.4 of the recovery strategy (Parks Canada Agency, 2012b).

4.2 Identification of critical habitat for Vole Ears Lichen

4.2.1 Geographic location

Additional critical habitat for Vole Ears Lichen is identified in Figure 4. This action plan identifies three areas of critical habitat in addition to the critical habitat sites identified in the recovery strategy for Vole Ears Lichen (Environment Canada, 2014) and the species’ 2020 action plan (Environment Canada, 2020). The presence of Vole Ears Lichen in Kejimkujik was not detected until after the regional recovery strategy was finalized (Environment Canada, 2014), consequently all sites in Table 5 of the Vole Ears Lichen recovery strategy are outside of Kejimkujik. These three additional sites include one site previously identified in the Kejimkujik action plan (Parks Canada Agency, 2017) and two new sites identified since 2017.

Critical habitat was identified using the criteria and methodology outlined in Section 7.1 of the recovery strategy (Environment Canada, 2014).

Text description

Figure 4 is a map showing critical habitat for Vole Ears Lichen (Erioderma mollissimum) within Kejimkujik National Park Seaside. Yellow shaded polygons indicate areas containing critical habitat, located within the park boundaries (shown as a green shaded polygon). Key reference points include St. Catherine’s River, St. Catherine’s River Beach, and Port Joli Bay. An inset map shows the park’s location on Nova Scotia’s south shore near Port Mouton and Shelburne.

4.2.2 Biophysical attributes

The biophysical attributes of critical habitat for Vole Ears Lichen in Nova Scotia are described in section 7.1 of the recovery strategy (Environment Canada, 2014). Critical habitat for Vole Ears Lichen occurs where the criteria and methodology described in section 7.1 are met (Environment Canada, 2014).

4.2.3 Examples of activities likely to result in destruction of critical habitat

Examples of activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat are described in section 7.3 of the recovery strategy (Environment Canada, 2014).

4.3 Proposed measures to protect critical habitat

Critical habitat identified for Eastern Ribbonsnake and Vole Ears Lichen within this action plan, and in recovery strategies for other species addressed in this plan, is legally protected from destruction as per section 58 of SARA. SARA requires that critical habitat identified within a federally protected areaFootnote 19 be described in the Canada Gazette within 90 days after the final recovery strategy or action plan is posted to the Species at Risk Public Registry. The prohibition against destruction under subsection 58(1) comes into force 90 days after that description is published.

For critical habitat on other federal lands (e.g., National Historic Sites or National Park Reserves), the competent minister must either issue a statement that existing laws provide effective protection or recommend an Order in Council to bring the subsection 58(1) prohibition into effect. If any portions of critical habitat are found not to be protected, and steps are being taken to protect them, those steps will be communicated through the Registry via the reports required under section 63 of SARA.

5. Evaluation of socio-economic costs and of benefits

The Species at Risk Act requires the competent minister to undertake an evaluation of the socio-economic costs of the action plan and the benefits to be derived from its implementation (s.49(1)(e)). This socio-economic assessment is narrow in scope, as it applies only to protected lands and waters in Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS, which are often subject to fewer threats (e.g., industrial activities) compared to other areas because the lands are managed to maintain and restore ecological and commemorative integrity. Further, this evaluation addresses only the incremental socio-economic costs and benefits of implementing the measures outlined in this action plan and does not include socio-economic impacts of existing activities or management regimes in those Parks Canada sites. It does not address total cumulative costs or benefits of species recovery in general nor does it attempt to conduct a full cost-benefit analysis as is done to support a regulatory initiative.

The protection and recovery of species at risk can result in both costs and benefits, which affect various groups of Canadian society in different ways. The proposed measures in this action plan seek a balanced approach to reducing or eliminating threats to species at risk populations and habitats. Potential socio-economic costs as well as the social and environmental benefits that may occur through implementation of this action plan are outlined below. Information for this summary was collected through cooperation, engagement, and consultation, and focuses on the potential impact to Indigenous communities, various partners, interest groups, volunteers, and visitors to Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS.

5.1 Costs

The total incremental cost to implement the measures outlined in Appendix B will be borne by Parks Canada out of existing salaries and goods and services dollars that are integrated into the operational management of the sites and thereby will not result in additional costs to society. Implementation of the measures in this plan is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints. Measures outlined in Appendix C will only be implemented through partnerships or if additional resources become available. Opportunities to reallocate existing budgets and/or acquire additional funds to support Indigenous engagement will be pursued in the spirit of collaboration.

Socio-economic costs to Indigenous communities and Kejimkujik and NHSs of Mainland NS visitors may result from implementation of this action plan. These costs were determined through consultation and discussion and wherever possible, minimized and/or mitigated. The main impacts of implementing this action plan were identified as restricted access to certain areas due to seasonal closures to protect species at risk and associated habitat. This may negatively impact visitors’ enjoyment and access to the landscape, and Indigenous communities’ access to certain areas for harvesting and traditional use. Kejimkujik visitors may also be impacted by the continued implementation of the firewood importation ban to mitigate and slow the spread of invasive species. Parks Canada has given these costs considerable examination and does not underestimate their potential significance to our Indigenous communities, various partners, interest groups, volunteers, and visitors. In many cases mitigations are currently in practice to minimize impacts and, where possible, have been anticipated and built into this plan to minimize impacts.

5.2 Benefits

Potential economic benefits of the conservation and recovery of species at risk at this site cannot be easily quantified, as many of the values derived from wildlife are non-market commodities that are difficult to appraise in financial terms. Wildlife, in all its forms, has value in and of itself, and is valued by Canadians for aesthetic, cultural, spiritual, recreational, educational, historical, economic, medical, ecological, and scientific reasons.

The conservation of species at risk is an important component of the Government of Canada’s commitment to conserving biological diversity and is important to Canada’s current and future economic and natural wealth. Measures in this plan help to meet the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy goal of protecting and recovering species and conserving Canadian biodiversity. It also contributes to the global goal of ensuring “biodiversity is sustainably used and managed and nature’s contributions to people, including ecosystem functions and services, are valued, maintained and enhanced, with those currently in decline being restored” (Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, December 2022).

The protected natural capital assets (forests, grasslands, wetlands, freshwater, coastal and marine areas) of national parks, national marine conservation areas, national historic sites, and national urban parks provide a flow of ecosystem services (e.g., climate regulation, provision of habitat, water supply and regulation) that benefit individuals and communities across Canada. Parks Canada works to sustain and improve the ecological condition of the national network of protected places. Efforts that improve species’ condition and their role in the ecosystem, such as recovery measures in this action plan, have an impact on the overall health of the ecosystem. For Kejimkujik, the potential annual value of ecosystem services has been estimated to range between $155 million and $1,152 million (medium value $629 million) (Mulrooney & Jones, 2023). Implementing the measures within this action plan will contribute to sustaining the valuable flow of ecosystem services to Canadians.

Measures presented in this action plan will contribute to meeting recovery strategy objectives for threatened and endangered species and will also contribute to meeting management objectives for species of special concern and cultural importance. Recovery Strategies, Action Plans and Management Plans for SARA-listed species are an integral part of species management aimed at species’ survival and recovery, maintaining biodiversity in Canada and conserving Canada’s natural heritage.